Organisers of the Olympic and Paralympic Games in Paris may be feeling a little queasy over their commitment to hold open water swimming in the scenic but often polluted Seine.

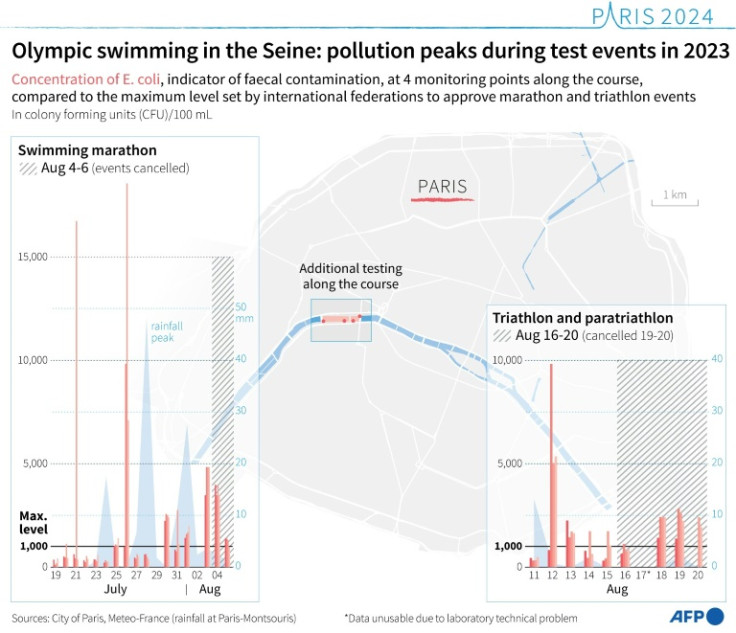

Last August, the marathon swimming test events were cancelled because the water was too dirty, as were the swimming legs on two of the four days of triathlon and para-triathlon tests.

The city of Paris has insisted “there is no plan B”.

The course for the men’s and women’s 10-kilometre events will start at the iconic beaux-art Pont Alexandre-III and, with the Invalides and Eiffel Tower in the background, head 1km down river past other famed attractions, including the Musee d’Orsay, and the Grand Palais.

Perhaps appropriately, it passes the newly-renovated Paris Sewer Museum and the more minimalist Pont d’Alma before looping back. The triathlon swims are shorter and will turn back sooner.

It is a route chosen to showcase the beauty of Paris.

It is also politically symbolic: swimming has been banned in the Seine since 1923 but various Paris mayors have vowed to open it up.

In 1990, when he was mayor before becoming French president, Jacques Chirac promised the river would “soon” be clean enough in which to swim and that he would celebrate by taking a dip. He never did.

The current mayor, Anne Hidalgo, a vigorous promoter of green initiatives, has also promised she will take the plunge before the Olympics start and that the public will be allowed to swim at three locations by 2025. She has yet to get her feet wet.

City officials argue that the quality of the water has improved, but none of the samples collected between June and September 2023 met European standards on the minimum quality of water for swimming.

The big problem is faecal matter. The bacteria in the water increases sharply when heavy rain sweeps debris and untreated wastewater into the river from the banks and the overflowing drains and sewers.

The city tests the water at 14 points. In 2022, water quality at three of them was judged to be “sufficient” but had deteriorated by last summer.

The open-water swimming last August was cancelled after heavy ran sent E. coli readings to six times the target level set by World Aquatics (FINA).

The city of Paris insisted they had “learnt” from the sampling problems at the test events.

National and local authorities are also investing 1.4 billion euros (more than $1.5bn) in five projects designed to clean the water.

According to a Paris city official, the failed tests for the team triathlon and, two weeks later, the para triathlon swimming were caused not by rain but by a “valve malfunction” in the Paris sewage system.

The weather remains the “main risk”, acknowledges the Paris town hall, which fears “exceptional rainfall”.

The only backup plan for the swimming is postponing the events by a few days.

“There is no solution to move the event, the triathlon and open water swimming will be held in the Seine next year,” Tony Estanguet, Paris 2024 organising committee, said after the cancellations last August.

For the athletes these are the Olympics and dirty water is a constant risk in open-water competitions.

At the end of the test event in 2019 ahead of the Tokyo Olympics, swimmers protested against the quality of the water in Tokyo Bay. Before the Rio Olympics in 2016, the polluted Guanabara Bay made headlines.

“A glittering setting,” Italian double world champion Gregorio Paltrinieri told Italian media in January. “Even if the water is dirty, I would rather swim in an electric atmosphere in the centre of Paris than in an anonymous stretch of water.”

After winning silver at the world championships in Qatar earlier in February, Frenchman Marc-Antoine Olivier said he was excited by the venue.

“People may be afraid of what’s in the water, but swimming in a historic place is going to be incredible,” he said. “Of course, a lot of people are going to try and create a bit of a buzz about the conditions we’re going to have in the water, but if we can swim then there’s no problem. They won’t take the risk of us swimming and someone catching something.”

The triathlons could become ‘duathlons’ as some did last summer.

“It would be a shame but we adapted to a duathlon,” said Briton Beth Potter, who won the individual test event.

AFP

AFP