AFP

India’s rising tide of Hindu nationalism is an affront to the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi, his great-grandson says, ahead of the 75th anniversary of the revered independence hero’s assassination.

Gandhi was shot dead at a multi-faith prayer meeting on January 30, 1948, by Nathuram Godse, a religious zealot angered by his victim’s conciliatory gestures to the country’s minority Muslim community.

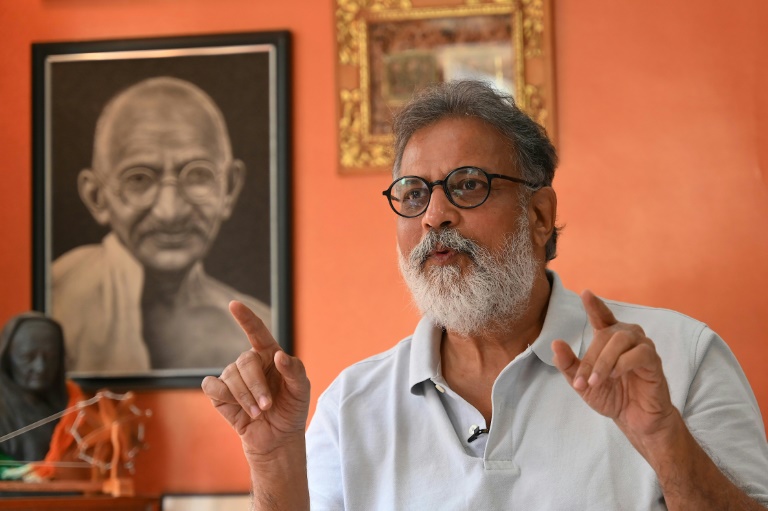

Godse was executed the following year and remains widely reviled, but author and social activist Tushar Gandhi, one of the global peace symbol’s most prominent descendants, says his views now have a worrying resonance in India.

“That whole philosophy has now captured India and Indian hearts, the ideology of hate, the ideology of polarisation, the ideology of divisions,” he told AFP at his Mumbai home.

“For them, it’s very natural that Godse would be their iconic patriot, their idol.”

Tushar, 63, attributes this tectonic shift to the rise of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Modi took office in 2014 and Tushar says his government is to blame for undermining the secular and multicultural traditions that his namesake sought to protect.

“His success has been built on hate, we must accept that,” Tushar added.

“There is no denying that in his heart, he also knows what he is doing is lighting a fire that will one day consume India itself.”

Today, Gandhi’s assassin is revered by many Hindu nationalists who have pushed for a re-evaluation of his decision to murder a man synonymous with non-violence.

A temple dedicated to Godse was built near New Delhi in 2015, the year after Modi’s election, and activists have campaigned to honour him by renaming an Indian city after him.

Godse was a member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a still-prominent Hindu far-right group whose members conduct paramilitary drills and prayer meetings.

The RSS has long distanced itself from Godse’s actions but remains a potent force, founding Modi’s party decades ago to battle for Hindu causes in the political realm.

Modi has regularly paid respect to Gandhi’s legacy but has refrained from weighing in on the campaign to rehabilitate his killer.

Tushar remains a fierce protector of his world-famous ancestor’s legacy of “honesty, equality, unity and inclusiveness”.

He has written two books about Gandhi and his wife Kasturba, regularly talks at public events about the importance of democracy and has filed legal motions in India’s top court as part of efforts to defend the country’s secular constitution.

His Mumbai abode, a post-independence flat in a quiet neighbourhood compound, is dotted with portraits and small statues of his famous relative along with a miniature spinning wheel — a reference to Gandhi’s credo of self-reliance.

Tushar is anxious but resigned to the prospect of Modi winning another term in next year’s elections, an outcome widely seen as an inevitability given the weakness of his potential challengers.

“The poison is so deep, and they’re so successful, that I don’t see my ideology triumphing over in India for a long time now,” he says.

“But it fills me with determination to keep fighting.”

AFP

AFP