Reuters

As extreme weather and human activity degrade the world’s arable land, scientists and developers are looking at new and largely unproven methods to save soil for agriculture.

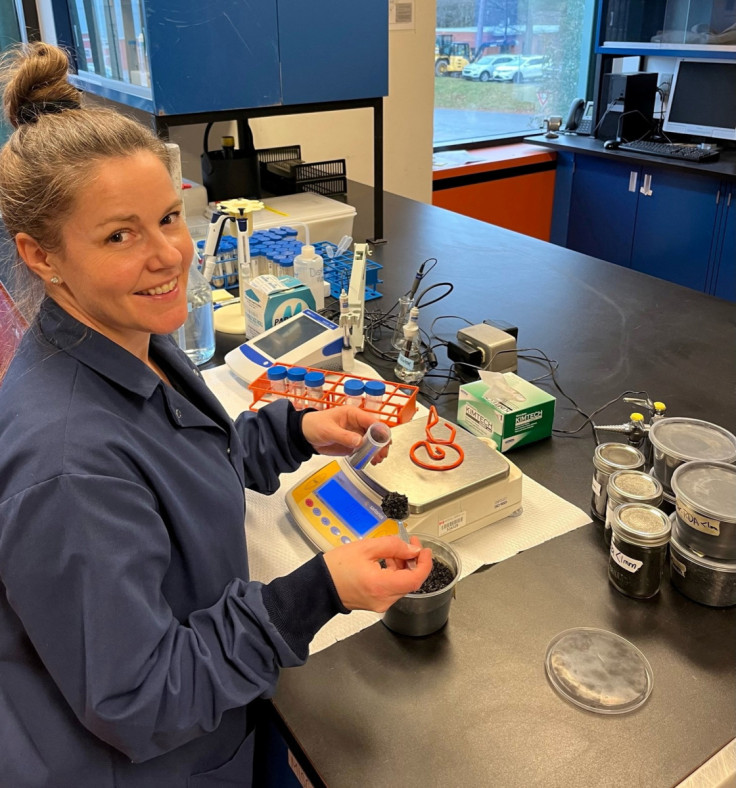

One company is injecting liquid clay into California desert to trap moisture and help fruit to grow, while another in Malaysia boosts soil with droppings from fly larvae. In a Nova Scotia greenhouse, Canadian scientist Vicky Levesque is adding biochar – the burnt residue of plants and wood waste – to soil to help apples grow better.

Long-established soil preservation techniques, such as tilling less and sowing crops during off-seasons, are proving no match for more frequent droughts, floods and temperature extremes. Soil erosion is depleting dirt’s ability to produce food, and could lead to a 10% loss in global crop production by 2050, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

New “soil amendment” solutions, which improve the physical properties of soil, may complement the traditional ways — if they prove profitable and effective.

Biochar, liquid clay and fly larvae droppings are all in limited commercial production. Development of such solutions has accelerated in recent years as soil degradation worsened, said Ole Kristian Sivertsen, chief executive of liquid clay company Desert Control, which made its first commercial sale in December.

Bayer AG, the world’s biggest seed company, is among the companies looking at new ways of regenerating soil through Leaps by Bayer, its venture capital unit, said Matthias Berninger, Bayer’s head of sustainability.

Bayer and other companies are already working on non-chemical ways to add nutrients to crops such as adding microbes into soil but products aimed at regenerating farmland go further. Some, like liquid clay and biochar add nutrients while also improving the ground’s ability to retain water, and require fewer applications than fertilizer.

“We have really started to focus on the soil in ways we traditionally wouldn’t have done,” Berninger said in an interview.

Dark Earths

Biochar is an artificial means of creating a carbon-rich product to boost soils, modelled after exceptionally fertile patches of Amazon rainforest called “Dark Earths” that were produced over time as a byproduct of cooking, animal decomposition and manure.

Biochar could be a “great opportunity” for trapping plant-sustaining carbon in the soil, Levesque said, adding that biochar also acts like a water sponge.

Her research, which started in 2012, has shown that clay soil treated with biochar emitted drastically less nitrous oxide, benefiting the atmosphere and trapping more carbon in the ground where it can boost plant growth.

Some types of biochar increased yields of greenhouse tomatoes and sweet peppers by 32% and 54% respectively, while requiring less fertilizer, due to biochar spurring reproduction of bacteria that benefit plant growth.

More research is needed, however, before scientists know how effectively biochar could regenerate different types of soils around the world, she said.

Norway-based Desert Control has spent 18 years and $25 million developing liquid clay to boost soil. Last year, it injected its product into a patch of U.S. desert, where the clay binds with sand to better retain water and nutrients.

Preliminary data from a five-year trial showed that in sand treated with clay, romaine lettuce hearts were on average 21-53% larger than romaine grown under the same conditions without clay, said Robert Masson, an official at University of Arizona’s Yuma County Cooperative Extension, who grew the plants.

In November, Desert Control signed a $182,000 contract with Limoneira Company, which will initially apply liquid clay to 4,000 trees on two of its citrus farms in the drought-stricken states of California and Arizona. Depending on results, Limoneira intends to expand application in the fourth quarter.

Each application lasts up to five years.

“Cover crops and no-till are good practices but they are far from enough,” Sivertsen said.

In Malaysia, Nutrition Technologies produces “soil conditioner” from frass – the waste and skin of Black Soldier Fly larvae. Composted frass led to a 12% increase in plant-nourishing soil organic matter, something that otherwise declines over time, according to the company’s research.

Nutrition Technologies, which started in 2015, sells an average of 200 tonnes of frass monthly in Malaysia, mainly to farmers who apply it to leafy greens, cucumbers and fruit, said Martin Zorrilla, the company’s chief technology officer.

The company raised $20 million in September, its most recent funding round.

While most Malaysian fertilizer producers now sell frass, volumes are still too low to draw the attention of global agriculture companies, Zorrilla said.

“Ultimately, soil is a living system, which is one reason it takes natural processes so long to build soil and why it is so easy to lose it,” he said.

Reuters

Reuters