AFP

For nearly eight years, driving for a ride-hailing platform and making deliveries helped Laine Carolyn pay her bills — but a sudden deterioration in health forced her to stop work and fall behind on rent.

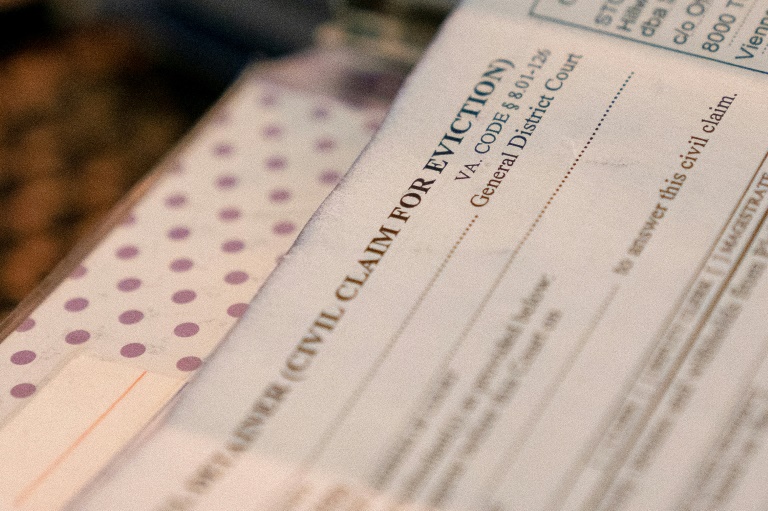

Carolyn, 32, is among an increased number of US tenants confronting eviction risks in the face of high inflation, elevated rents and with the end of pandemic-era aid.

The country sees 3.6 million eviction cases filed in a typical year, said Peter Hepburn, associate director of Eviction Lab at Princeton University. But that number slowed to a trickle during the pandemic.

Now, with Covid-era legal protections and assistance lifted, it is surging again, Eviction Lab’s figures show.

At courthouses in Virginia, tenants living paycheck-to-paycheck told AFP how an unexpected accident or medical bill was enough to land them before a judge with an eviction filing.

Carolyn said she owes over $10,000 in rent and other fees. But she could not return to employment after being diagnosed with Graves’ disease and hospitalized last November.

“It was giving me double vision and it wasn’t safe for me to drive,” she said.

“There is brain fog, and it makes it almost impossible to think,” the Alexandria resident added.

Carolyn said that she cannot afford to appeal her eviction case, which requires her to repay her rent — so she is out of options. Now she is waiting for the axe to fall.

There has been a “steady increase” in eviction filings over the last year, and nationwide numbers are now close to where they were before the pandemic, said Hepburn of Eviction Lab.

In the 10 states and 34 cities that the group tracks, the number of such cases filed rose from around 6,600 in April 2020 during the pandemic to over 96,800 in January.

Carolyn had worked out a payment plan with her landlord but it became increasingly hard to work as her health worsened: “I just couldn’t make enough money.”

“I managed to make $800 before I really got too sick to work. I had to choose between paying that towards rent or having food and some medicine,” she said.

“There is anger, there is frustration, there is guilt and even some shame that I probably shouldn’t be taking on because… I really am actually sick, and it’s something I gotta finish accepting,” she added.

Over a third of the US population rent their homes.

“We haven’t even seen a flattening out yet” after a dramatic rise in eviction filings, said Mary Horner, senior staff attorney at Legal Services of Northern Virginia (LSNV).

Some households were approved for rental assistance that never arrived as funding dried up, resulting in arrears of over $10,000.

But there are also many “who owe lower amounts, who simply cannot keep up with the increase in rents,” Horner said.

“Rents are a lot higher than they were. Inflation has made food more expensive… The money that families had before is just being stretched much more thinly,” she added.

In Richmond, Virginia, the situation is also grim with record-low vacancies and high rent increases, said Martin Wegbreit, litigation director at Central Virginia Legal Aid Society.

Richmond ranked second among large cities for eviction rates in 2016.

“It’s a perfect recipe for tenants being squeezed even more now than they were before the pandemic,” he added.

Yolanda Wilson, 45, said she had to get a new vehicle — which she needed for work — with money meant for rent after her car caught on fire.

The situation landed her with an eviction filing and some $2,900 to repay.

“Even if I have a plan (for repayment)… I feel anxious,” she said.

Growth in rental prices has cooled but shelter costs still accounted for over 70 percent of the increase in consumer prices in February.

For many, the eviction process is traumatizing, said Horner of LSNV.

“Nearly all tenants are unrepresented… They don’t necessarily know what their rights are,” she said.

To appear in court, many have to take time off work, often bringing their children along as they lack childcare.

A 25-year-old tenant who gave her name only as Diamond returned to work shortly after having a baby in hopes of avoiding eviction.

“It’s stressful because I have a small child,” she told AFP. “Nobody wants to be out of a place to live.”

While President Joe Biden’s administration has announced actions to boost fairness in the rental market, it will take time for this to trickle down.

Black renters face greater risks, women are more likely to be listed as defendants and renters with children are at greatest risks of eviction, Hepburn noted.

“Economic factors go potentially a long way to explaining it, but we absolutely can’t eliminate the possibility that discrimination plays a part as well,” he said.

“When you’re filed against for eviction, that record follows you,” he added.

AFP

AFP