KEY POINTS

- Researchers looked into the death of a man who died of rabies from a bat bite

- They found that the man had an “unrecognized impaired immunity”

- It was the “first reported failure of rabies PEP in the Western Hemisphere”

A man died of rabies in Minnesota even though he had gotten the postexposure prophylaxis treatment, and researchers worked to find out why.

The researchers reported the case in their paper, which was recently published in Clinical Infectious Diseases. According to them, the 84-year-old man woke up to find a bat biting his hand in July 2020. He washed his hand with soap and water, but days later, testing of the bat revealed that it was actually positive for rabies.

The man hadn’t been vaccinated for rabies before, but he got the postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) treatment because the bat tested positive. His wife also received it since she was sleeping beside him when the bat bit him. He then got three more doses of the vaccine.

The PEP protects people from developing rabies, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It should be given “as soon as possible” after the bite. If administered properly and soon enough, it is said to be 100% effective at preventing rabies.

In the case of the man, however, he developed symptoms on Jan. 7, 2021, some five months after the bite occurred. His condition worsened, and he had to be hospitalized a week later on Jan. 14. He died on Jan. 22, and authorities confirmed that he had rabies.

“This is the first reported failure of rabies PEP in the Western Hemisphere using a cell culture vaccine,” the researchers wrote.

So what happened?

To find out, researchers conducted a thorough investigation that involved scouring medical and autopsy records and conducting whole genome sequencing.

They eventually determined that the man’s age and the medical conditions he had may have something to do with what happened. Apparently, the man had Type II diabetes, coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease.

Importantly, he had an “unrecognized impaired immunity,” which they said was the “most likely explanation” for why he had the breakthrough infection despite promptly getting the PEP.

“Clinicians should consider measuring rabies neutralizing antibody titers after completion of PEP if there is any suspicion for immunocompromise,” the researchers wrote.

The rabies vaccine is still an important tool to save lives. It has been around for over 100 years, and this has helped cause a major drop in rabies-related deaths in the U.S. However, such deaths continue to happen in other countries that lack public health resources and access to treatment.

“Human rabies is a 100% vaccine-preventable disease, yet it continues to kill,” the World Health Organization (WHO) said. “Rabies vaccinations are highly effective, safe and well tolerated.

Worldwide, rabies causes some 59,000 deaths each year. Only recently, New Zealand, which was one of the few countries that are considered to be free from rabies, logged its first case of the illness in a visitor who contracted it overseas.

Rabies cases are also quite rare in the U.S., which logs one or two deaths per year — much lower than the 100 annually recorded in the early 1900s. The current deaths also tend to occur in those who did not seek prompt medical care.

A quarter of the 127 cases from 1960 to 2018 were also in people who got dog bites during international travel.

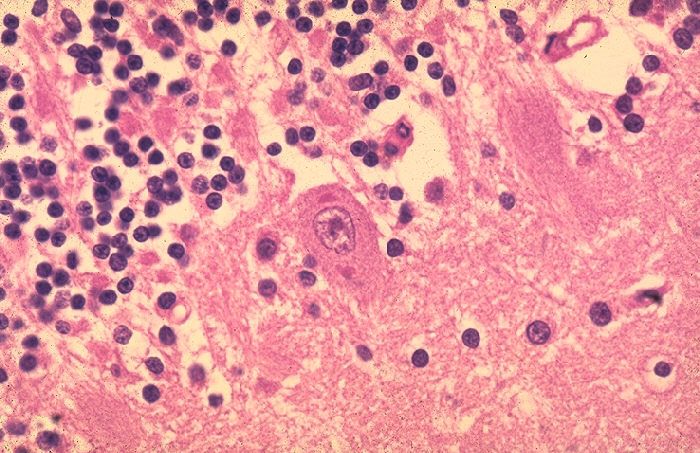

CDC/Dr. Makonnen Fekadu