AFP

Every morning for the last 42 years, Piet Kempenaar has cast a careful eye over the Dutch sky before releasing a brake and “steering” the giant blades of his centuries-old mill into the wind.

To match the force, he adjusts the sails of De Kat (The Cat), the world’s last remaining mill using wind power to crush rocks into fine dust and make paint pigment — just as it was done almost 400 years ago.

Driven by a system of wooden gears, ropes and pulleys, two massive grinding stones together weighing 10 tonnes churn and crush rocks for hours on end, until they become colourful pigments with enticing names like lapis lazuli, terre verte, umber and burnt sienna.

Now retired and leaving most of the paint-making business to his son Robert, Kempenaar still cuts the quintessential figure of a seasoned Dutch “colourman” in a cap, blue workman’s jacket streaked with pigment dust, and a pipe angled in the corner of his mouth.

Behind him, De Kat, standing on the spot where rocks were first ground into pigment around 1646, creaks and groans as the four giant blades power the grinding stones in a never-ending circle.

The original mill burnt down in 1782 before being rebuilt. De Kat has been reconstructed and repurposed over the centuries for a variety of roles including a chalk storage space at one stage, before resuming its rock-crushing duties in 1960.

Kempenaar has leased De Kat from the local milling association since 1981 for his pigment-making business, which attracts thousands of buyers every year.

“I am not interested in painting, but I am obsessed with pigments,” the 73-year-old Kempenaar told AFP at the famous mill in the picturesque but tourist-heavy Zaanse Schans north of Amsterdam.

In his rugged hands, Kempenaar holds a block of a famous blue pigment favoured by a Dutch master.

“Here we have the king of the blue. It’s a half-diamond from Chile or Afghanistan. You’re talking about lapis lazuli, used by Johannes Vermeer,” he said.

“Vermeer had the money — he could pay for it. Back then, this was literally worth its weight in gold”.

Dozens of pigments made at De Kat are neatly stacked on shelves — terre verte or “green earth” from Verona, dark umber from Cyprus and carmine red, made from grinding up female cochineal insects, from the Canary Islands.

“We grind pigment the old way here. That’s why people from all over the world come to buy from us. It’s unique,” Kempenaar said.

“And it hasn’t changed in almost 400 years.”

Art experts say many of the pigments used by Dutch masters like Vermeer and Rembrandt almost certainly came from “dye mills” dotted around the Dutch landscape at the time.

This includes the precious lapis lazuli which produced the ultramarine blue paint for the apron of Vermeer’s famous work The Milkmaid.

Today, De Kat is the last link to the original way of paint-making before the process was industrialised around 1850, experts say.

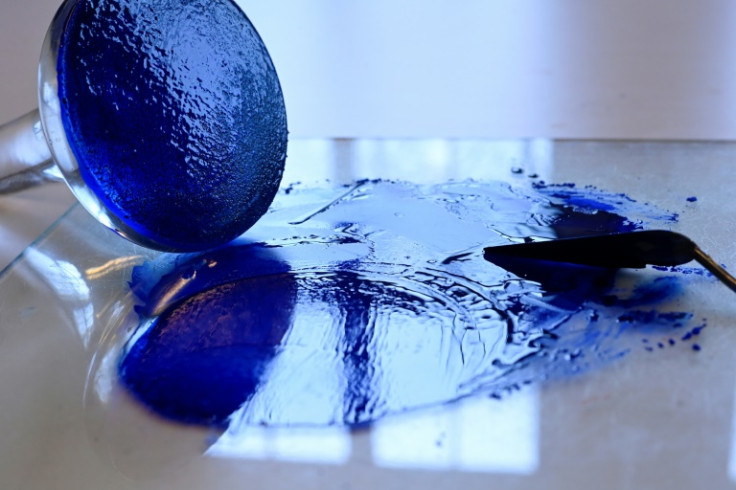

At Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, some 20 kilometres (12.5 miles) to the south of the Zaanse Schans, art lecturer Peter Pelkmans has been preparing a paste of lapis lazuli and linseed oil to make ultramarine blue paint.

At the museum’s Teekenschool (Drawing School) workshop, amateurs and artists alike can learn how to prepare paint the traditional way using De Kat’s pigment.

“We give people a chance to take a step back in time,” Pelkmans told AFP before mixing another colour, this time a burnt sienna, much loved by Rembrandt.

Rembrandt was known to grind most of his own pigment in a giant iron mortar in his studio and used a cheaper alternative called “smalt” as a substitute for the precious and more expensive lapis lazuli.

Vermeer’s ultramarine blue pigment was however made from lapis lazuli, almost certainly ground in a windmill, Pelkmans said.

He explained just how precious the prized colour was.

“Often the blue was left as the last part of a commissioned painting. The artist would only add it once he had been paid in full,” Pelkmans laughed.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP