AFP

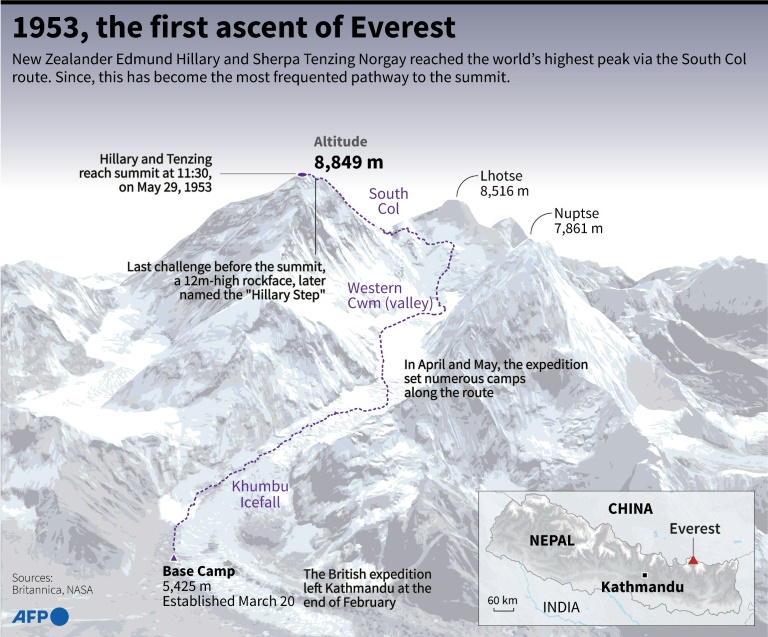

Seventy years ago, New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepali Tenzing Norgay Sherpa became the first humans to summit Everest on May 29, 1953.

The British expedition made the two men household names around the world and changed mountaineering forever.

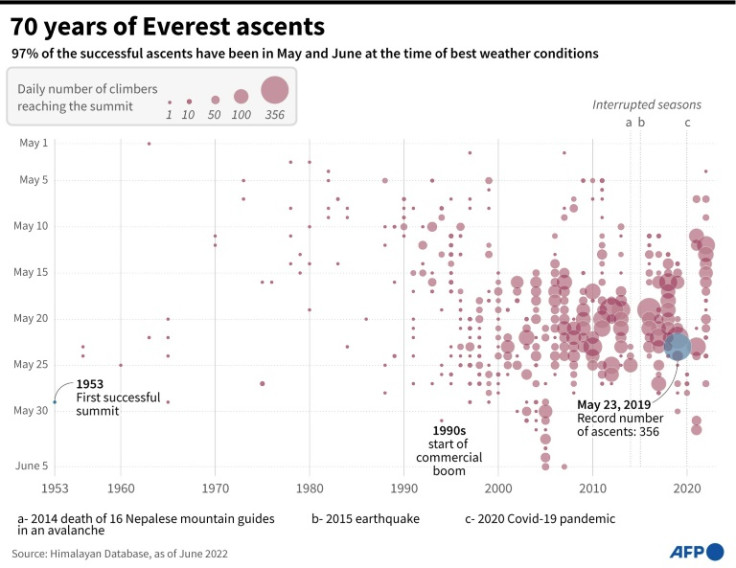

Hundreds now climb the 8,849-metre (29,032-foot) peak every year, fuelling concerns of overcrowding and pollution on the mountain.

AFP looks at the evolution of the Everest phenomenon.

Initially known only to British mapmakers as Peak XV, the mountain was identified as the world’s highest point in the 1850s and renamed in 1865 after Sir George Everest, a former Surveyor General of India.

On the border of Nepal and China and climbable from both sides, it is called Chomolungma or Qomolangma in Sherpa and Tibetan — “goddess mother of the world” — and Sagarmatha in Nepali, meaning “peak of the sky”.

The 1953 expedition was the ninth attempt on the summit and it took 20 years for the first 600 people to climb it. Now that number can be expected in a single season, with climbers catered to by experienced guides and commercial expedition companies.

The months-long journey to the base camp was cut to eight days with the construction of a small mountain airstrip in 1964 in the town of Lukla, the gateway to the Everest region.

Gear is lighter, oxygen supplies are more readily available, and tracking devices make expeditions safer. Climbers today can summon a helicopter in case of emergency.

Every season, experienced Nepali guides set the route all the way to the summit for paying clients to follow.

But Billi Bierling of Himalayan Database, an archive of mountaineering expeditions, said some things remain similar: “They didn’t go to the mountains much different than we do now. The Sherpas carried everything. The expedition style itself hasn’t changed.”

The starting point for climbs proper, Everest Base Camp was once little more than a collection of tents at 5,364 metres (17,598 feet), where climbers lived off canned foods.

Now fresh salads, baked goods and trendy coffee are available, with crackly conversations over bulky satellite phones replaced by wifi and Instagram posts.

Hillary and Tenzing summited Everest on May 29 but it only appeared in newspapers on June 2, the day of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation: the news had to be brought down the mountain on foot to a telegraph station in the town of Namche Bazaar, to be relayed to the British Embassy in Kathmandu.

In 2011, British climber Kenton Cool tweeted from the summit with a 3G signal after his ninth successful ascent. More usually, walkie-talkie radios are standard expedition equipment and summiteers contact their base camp teams, who swiftly post on social media.

In 2020, China announced 5G connectivity at the Everest summit.

Warming temperatures are slowly widening crevasses on the mountain and bringing running water to previously snowy slopes.

A 2018 study of Everest’s Khumbu glacier indicated it was vulnerable to even minor atmospheric warming, with the temperature of shallow ice already close to melting point.

“The future of the Khumbu icefall is bleak,” its principal investigator, glaciologist Duncan Quincey, told AFP. “The striking difference is the meltwater on the surface of the glaciers.”

Three Nepali guides were killed on the formation this year when a chunk of falling glacial ice swept them into a deep crevasse.

It has become a popular cause for climbers to highlight, and expedition companies are starting to implement eco-friendly practices at their camps, such as solar power.

Click, post, repeat — the climbing season plays out on social media as excited mountaineers document their journey to Everest on Facebook, Instagram and other social media platforms.

Hashtags keep their sponsors happy and the posts can catch the eyes of potential funders.

That applies to both foreign climbers and their now tech-savvy Nepali guides.

“Everyone posts nowadays, it is part of how we share and build our profile,” said Lakpa Dendi Sherpa, who has summited Everest multiple times and has 62,000 Instagram followers.

Veteran Nepali guides Kami Rita Sherpa and Pasang Dawa Sherpa both scaled Everest twice this season, with the latter twice matching the former’s record number of summits before Kami Rita reclaimed pole position with 28.

There are multiple Everest record categories for first and fastest feats of endurance.

But some precedents are more quixotic: in 2018, a team of British climbers, an Australian and a Nepali dressed in tuxedos and gowns for the world’s highest dinner party at 7,056 metres on the mountain’s Chinese side.

AFP