AFP

Nations opposed to deep sea mineral mining and those in favor of exploiting the oceans’ depths butted heads in Jamaica on Wednesday, with both sides arguing their position would help protect the planet.

Members of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a little-known global body tasked with regulating the vast ocean floor, are locked in a heated debate over the future of deep sea mining at their annual meeting in Kingston.

“We cannot and must not embark on a new industrial activity when we are not yet able to fully measure its consequences, and therefore risk irreversible damage to our marine ecosystems,” said Herve Berville, French secretary of state for seas.

“Our responsibility is immense, and none of us in this room will be able to say that we were unaware of the collapse of marine biodiversity, the rise in sea level or the sudden increase in ocean temperature,” he warned during a debate.

This year’s meeting, set to end Friday, comes after a July 9 deadline triggered by the small Pacific state of Nauru.

That legal step has created a new pressure to adopt a deep sea mining code and given fuel to opponents who hope to block the practice outright.

The ISA is made up of 168 member states, as well as the European Union.

Under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the body is responsible both for protecting the seabed in areas beyond national jurisdiction and for overseeing any exploration or exploitation of resources in those zones.

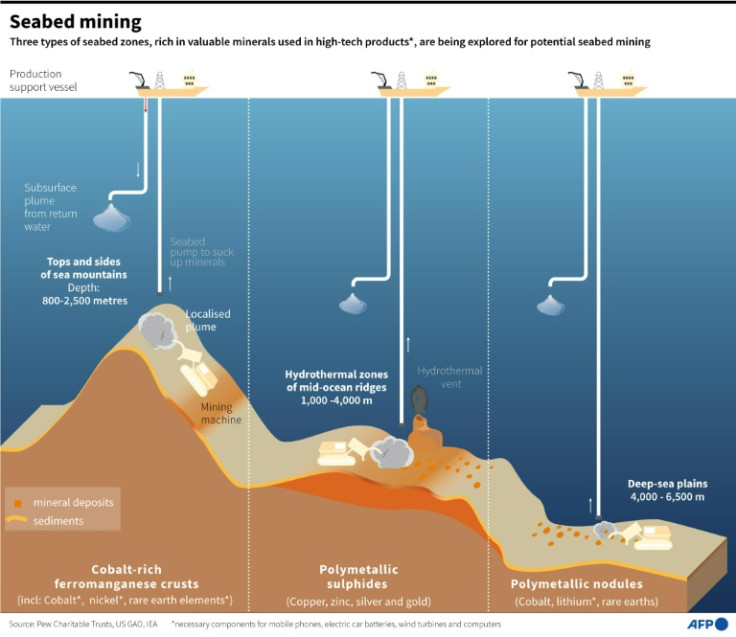

Some countries want to hurry up and begin retrieving the rock-like “nodules” scattered across the seafloor, which contain minerals important to battery production such as nickel, cobalt and copper.

“We have a window of opportunity to support the development of a sector that Nauru considers has the potential to help accelerate our energy transition to combat climate change,” argued the island nation’s president Russ Joseph Kun.

But NGOs and scientists say that trawling the deep seas could destroy habitats and species that may still be unknown or potentially vital to ecosystems.

They also say it risks disrupting the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon dioxide emitted by human activities, and that its noise interferes with the communication of species such as whales.

Around twenty countries, including France, have asked for a “precautionary pause” on deep sea mining, and have recently gained some political momentum.

Greenpeace’s Louisa Casson hailed new calls by Brazil and Canada for such a moratorium, telling AFP that “cracks are appearing in what has to date been a fortress for industry interests.”

But several countries have resisted hitting the pause button, notably China, which has succeeded thus far in blocking any official debate on the matter.

Mark Brown, the prime minister of the Cook Islands, argued that the “global community needs to use every tool at its disposal” to fight climate change.

But he called for any path forward to be done “responsibly and sustainably for the longterm wellbeing of our people and the preservation of our unique marine environment.”

The ISA Council, the decision-making body on contracts, has previously given out several permits for seabed exploration, but with the passing of the July 9 deadline, any member state can now apply for a mining contract for a company it sponsors.

Last week, the 36-member Council gave itself the target of adopting the mining code in 2025, but without agreeing on how to examine contract requests in the meantime, prompting criticism of a “legal vacuum.”

Nonetheless, Nauru says it will apply “soon” for a contract for Nori, a subsidiary of Canada’s The Metals Company, which seeks to harvest “polymetallic nodules” in the Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone (CCZ) in the Pacific.

In March, however, the ISA Council noted that commercial exploitation “should not be carried out” until a mining code was in place.

The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition’s Sofia Tsenikli said Wednesday that Nauru’s “ultimatum has not worked out.”

“The mining code is far from developed and the majority of states in the council have stated their opposition to mining in the absence of regulations,” she added.

Casson of Greenpeace, for her part, viewed the latest developments optimistically, saying “the world is fighting back against deep sea mining.”

“There’s a big fight ahead, but the fight is on.”

AFP