A decade after a wave of bankruptcies all but wiped out the German solar industry, the sector is looking to reestablish itself in the face of stiff competition from abroad.

Overproduction in China and massive government subsidy programmes in the United States mark the struggle to stay profitable for a business that used to boom in Germany.

In Bitterfeld-Wolfen, a solar cell plant opened in 2021 by the Swiss group Meyer Burger on the site of defunct German producer Q-Cells is a sign of a possible renaissance.

“We managed to recruit a number of former employees in the sector, and we are benefitting from their know-how,” the director of the Meyer Burger factory, Jochen Fritsche, told AFP.

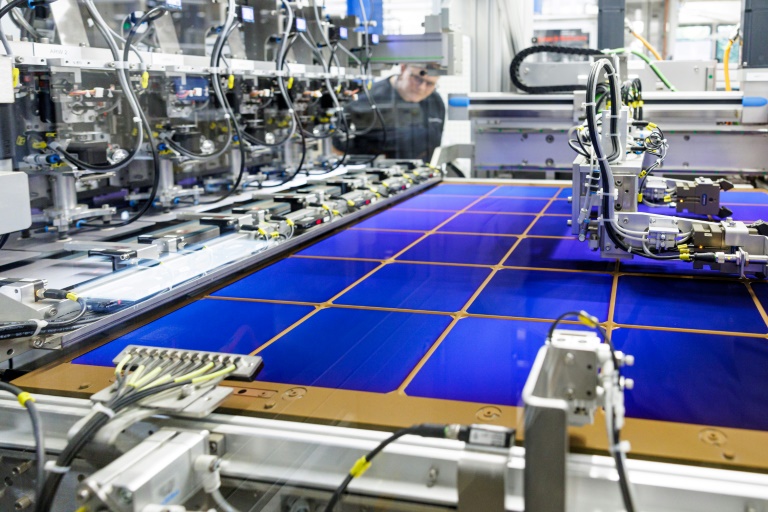

At the plant in the eastern German city, a million of the blue cells roll off the line each day, ready to be assembled into the modules that make up solar panels.

Production at the factory is largely automated, with just some 50 employees overseeing the non-stop manufacturing process via computer screens.

First, the silicon wafers that form the basis of the cells are dipped in a chemical solution. Then they are given a reflective grey coating, dried and cut in two.

The outcome of this high-precision industrial process — the details of which are closely guarded by Meyer Burger — is a cell which is said to yield 20 percent more energy than the competition.

“Technology is the core of our business and it’s what is allowing us to rebuild production in Europe,” Gunter Erfurt, Meyer Burger’s CEO, told AFP.

The group’s factory is located at the heart of what was once heralded as “Solar Valley”, an area in the middle of former communist East Germany that hosted a high concentration of solar energy businesses in its heyday in the 2000s.

German manufacturers were global leaders in solar at the time, carried along by healthy government subsidies. But the public funding was slashed in 2010, leading many of the businesses to go bust.

Thousands of jobs were cut in Solar Valley, while Chinese competitors took the top spot in the industry.

Today, Chinese companies make up an estimated 80 percent of photovoltaic production worldwide, just as Germany is looking to reduce its reliance on the Asian giant and expand renewable energy capacity.

Berlin’s aim to produce 80 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2030 has been boosted by the revival of its domestic industry.

Between January and September 2022, production of solar panel modules in Germany was 44 percent higher than in the previous year.

Despite the recent uptick the challenges for the industry in Germany remain significant — not least a fierce international subsidy race.

In the United States, President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act has lined up billions of dollars to boost production in solar and other technologies.

The European Union responded in March this year with its own plan that would make it easier to financially support green industries, but the project is still awaiting final approval from member states and the European Parliament.

“We are under the impression that Europe is always behind… in the United States, everything is faster,” said CEO Erfurt.

Earlier this year, Meyer Burger decided to expand production in the United States, while it is asking for a 200,000-euro ($211,779) subsidy to up capacity in Germany.

Manufacturing costs in Europe remain higher than elsewhere. “Europe is not competitive enough in industries which are energy-intensive, but not particularly sophisticated,” said Georg Zachmann from the Bruegel think tank.

What is more, overcapacity in China is pushing prices for solar modules lower and making it harder for European companies to make the numbers add up.

The challenge has already been too much for some. Nordic group Norwegian Crystals filed for bankruptcy in August, underlining the risks for the European sector as it looks to grow again.

AFP

AFP