An unvarnished oral history of the birth of National Post, direct from 22 people who helped build it, although many more were important to its creation

Article content

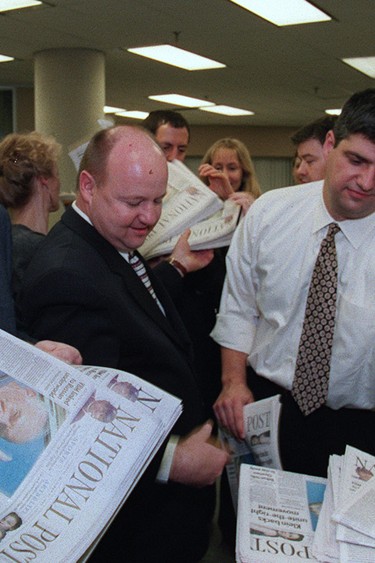

Early in the morning of Oct. 27, 1998, after an exhausting and exhilarating night, something remarkable was happening: the first copies of the first edition of National Post were being gobbled up across Canada.

Newspaper boxes were stripped bare, newsstand vendors screamed for more, copies were shared, stolen, resold for profit.

During the night, the new national newspaper, likely the last such startup in North America, had rolled off printing presses in nine cities dotted across 4,400 kilometres.

Advertisement 2

Article content

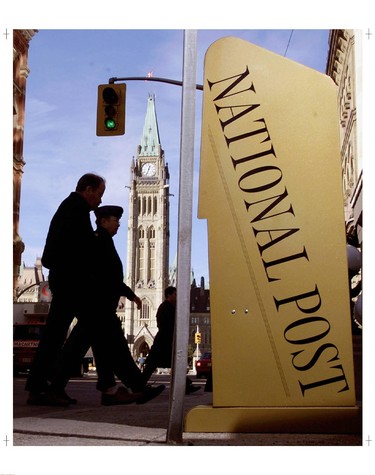

Not only was National Post introduced that day as a fresh voice in an overly comfortable media landscape, but an intense newspaper war was declared.

Launching a new daily newspaper was an astonishing achievement and although it received great fanfare and ballyhoo, many media pundits and competitors declared it a doomed enterprise: Competition is too great, newspaper wars are costly, readers won’t change habits, Canadians won’t stomach a conservative stance, it’s owned by that horrid media baron Conrad Black… Against such clatter, perhaps just as surprising as its birth is its ongoing success.

The newspaper edition still rolls off presses, but National Post has ever-widening reach as a digital platform of news, videos, podcasts, and newsletters, all a testament to its inception.

Perversely counterintuitive, the Post was a beautiful, innovative, well-crafted production forged in a madcap frenzy, wildly flying by the seat of its pants.

If it was built under less dedicated ownership, if its leaders were less imaginative and its staff more restrained, if it was a less energetic, anarchic, and adventurous crew, it surely would have run aground in a whimpering mess. The doomsayers would have been right.

Advertisement 3

Article content

But it didn’t and they weren’t.

Here is that story.

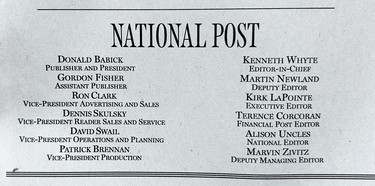

This is an unvarnished oral history of the birth of National Post. It comes direct from 22 people who helped build it from top to bottom, although 10 times that number were important to its creation. Some comments were edited for brevity and clarity. All titles are the person’s position at time of launch.

DON BABICK, president of Southam Inc.: It began with a phone call from Conrad Black that came out of the blue. I was six months into the job as the president of the company. In the spring of 1997, March, I happened to be in Palm Springs and I got a call from Conrad, and we had a long chat about him wanting to start a national newspaper to be another voice other than the Globe and Mail.

I was of the opinion it was going to be a struggle financially for us to launch a national newspaper and not lose a lot of money for a lot of years. But he wanted it done, so I started the process with Gordon Fisher, David Swail, and a few others, to come up with the first rumbling of a plan. He didn’t give us a lot of time to do it.

GORDON FISHER, vice-president of editorial at Southam: I had been working with and for Conrad Black for some time and I was very aware he had ambitions to have a national newspaper. Southam, as a newspaper company, had no foothold in Toronto of any kind and you needed to be in Toronto to get the attention of major advertisers. The Globe and Mail was obviously a target. He would have probably preferred to buy the Globe.

Advertisement 4

Article content

I was on vacation and got the call from Conrad — one of two he made that day, the other being to Don Babick — revealing that he had decided to go forward with the creation of a new national newspaper. His instructions were to return home and put meat to that vision.

CONRAD BLACK, owner of Southam newspaper chain and founding proprietor of National Post: It was an anomalous situation to have the country’s leading newspaper company have no newspaper in the country’s leading city… I saw that the pretense of the Globe and Mail to being a national newspaper was in some measure an elegant scam. It was nothing of the kind. I thought they were vulnerable, and I thought we could absolutely hammer them outside Toronto. Everybody was happy: The Sun had their niche as a tabloid, the Star had theirs, and the Globe had theirs, and it was a nice little cartel, but we interrupted it.

FISHER: The first outline that we took to him was for a newspaper of about 32 pages, maybe a page of sports, heavy on finance and general interest content, heavy on opinion, but with most of it coming from other sources, not new hires. I underestimated Conrad’s ambitions.

An early proposal, in a blood-red binder, is dated May 23, 1997, and marked “CONFIDENTIAL”. The report is titled “National business daily project update.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

KEN WHYTE, editor-in-chief: I was always Conrad’s candidate for editor, so I never really had any doubt about my role from our first conversation. But I was an outsider at Southam. I worked for Saturday Night magazine. There was a big chain of newspapers from coast to coast with a lot of really experienced newspaper people involved, and they naturally wanted one of their own to head up the project. Don Babick and Gordon Fisher wanted both Michael Cooke (editor of the Province in Vancouver) and Kirk LaPointe (editor of the Hamilton Spectator) to be involved. I was a magazine guy and I had never worked at a newspaper; I wouldn’t have trusted me either. I was asked by Southam leadership at one point to maybe step aside and let Michael drive the bus. But I never had any instructions to the contrary from Conrad.

BABICK: I don’t remember contemplating that. Look, Ken Whyte was Conrad’s choice to be the editor of the Post. Ken was the editor of Saturday Night, which we owned, so we knew of Ken, were happy with Ken. They were like-minds from an ideology and political point of view, which was going to help. Ken and I did get together privately for dinner, and we might have had a little bit of disagreement on reporting lines or something, but we steamed that all out.

Advertisement 6

Article content

FISHER: That was certainly a discussion preceding launch. And for sure, before Conrad landed on Ken Whyte, it is true that many internal execs were pushing for Michael Cooke. I was leaning that way as well. I appreciated Ken’s instincts and talent, but he could be a morose individual hard to communicate with. Michael, on the other hand, was an ebullient communicator and strong leader.

But once Conrad made his choice known, I don’t remember any sort of pushback. It was pretty obvious that Ken was going to be the editor. He had the advantage of being an outsider, a natural sense of story, and strong relationships with many great writers.

WHYTE: I probably didn’t trust the guys at Southam as much as I should have, because I think they were well intentioned. I got the sense, especially in the early stages, that I was the outsider. I never really felt 100 per cent part of that team — and I’m willing to believe it was at least half my fault.

Things moved pretty quickly. There were meetings through 1997 where we did some planning work, just high-level conceptual stuff: what would a national newspaper look like? What should a new newspaper do or not do?

KIRK LAPOINTE, executive editor: In the early stretch, it was going to very well produced but it was also going to be small. Southam didn’t have the technical facilities in Toronto (to create prototype newspapers) and so Ken Whyte and Michael Cooke and others came down to Hamilton and we worked in the Media Lab at the back of the Hamilton Spectator, where I was the editor. We needed someplace to design it and we were able to do that with a lot of privacy.

Advertisement 7

Article content

WHYTE: We had sketches for what the paper was going to look like, but we didn’t have a complete architecture, we didn’t have things designed, we didn’t know how everything was going to operate, we didn’t know where all the news was going to come from. There’s a lot of things to work out by a bunch of people who hadn’t worked together before.

Around the same time as the Hamilton sessions, an internal report dated Aug. 1, 1997, titled “Proposal for a new national Canadian newspaper for Southam Inc.” was distributed to executives at Southam and Hollinger, Black’s media holding company.

WHYTE: At an early-stage meeting about the Post, after we’d done some business plans… we met with the Hollinger board to talk about it. At one point in the meeting Conrad went around the table and asked Don Babick whether he thought this thing was a runner or not, and Don said ‘Well, if we get the product right, yeah, I think it’ll work.’ And then he asked Dennis Skulsky, who was going to be running the circulation side, and he said ‘Yeah, I think this is a great idea, if the product’s right.’ And then we went through advertising, and to Gordon Fisher, and everyone had the same response, that it was a great idea as long as the product was right. So, I decided at that moment that we had to do absolutely everything we can to make sure the product was right.

Advertisement 8

Article content

BABICK: We did have another final meeting of the Southam board’s executive committee, which included Conrad, naturally, myself, David Radler and a couple outside directors: Are we really going to go ahead with this?

One of the issues all along was we were going to lose a lot of money before we ever made a dime of profit, so we had to get Conrad to understand and agree to what that number might be. I believe I said there’s a possibility that we could lose up to $150 million over the next five years. We probably lost more than that. It was Conrad’s dream, and I was pretty immersed as a believer of the dream by that time.

WHYTE: I think it was February 1998 when things became real. We had approval from the board that we were going to go ahead. I went that spring to the U.K. We learned a lot from the Daily Telegraph (a large British newspaper Black also owned) and I spent about a week or 10 days in that newsroom — it was the only time I’d ever in my life spent in a newsroom before the National Post. I met the editor-in-chief, Charles Moore, and I sat in with the editorial board and a whole bunch of other higher ups at the newspaper. But after a day or two I gravitated towards Martin Newland, who was running the news desk. They seemed to be just having a lot more fun than anyone else at the Telegraph. He was a good old-style newsman, as good as I’ve ever met.

Advertisement 9

Article content

MARTIN NEWLAND, Deputy Editor: Conrad sent Ken here to see how the Telegraph worked and he listened and watched and then he took me out to lunch and talked about news and everything, and at the end of the lunch he just dropped a query: ‘Are you wedded to the UK?’ I didn’t hear anything for a month and then he called and said how would I like to go out to Canada and help him launch a paper. I’ve always had an instinct for adventure. I talked to my wife and called him back the next day and said I’ll come.

FISHER: Martin Newland was pretty particular, he needed certain assurances, but he was worth every penny — he changed the dynamic within the growing newsroom.

BLACK: The profitability of the Southam group rose very quickly, I mean it literally tripled in two years, so we had plenty of money. I was prepared to identify a relatively large number as an acceptable start-up cost, providing the project was objectively a success.

BABICK: In April 1998 we held the press conference to announce we were actually going to launch a new national newspaper, and we held it in Vancouver for a specific reason — we weren’t going to do it in Toronto.

Babick’s formal announcement on April 8, 1998, of a hard plan for a new newspaper pushed ideas from theoretical to practical. Whyte was publicly confirmed as editor on May 1.

Advertisement 10

Article content

LIZA COOPERMAN, assistant to the editor-in chief: I was working as Ken’s assistant at Saturday Night magazine and he kept disappearing for chunks of time and there were rumours he was talking to Conrad Black about this possible newspaper. A year into my job, Ken asked me to go with him, so I think I might have been employee number one, after Ken. It was just the two of us who moved up to the office in Don Mills (in north Toronto). Martin Newland and Kirk LaPointe joined us shortly after and we were kind of holed up in a couple of offices and cubicles at that big Don Mills space that would eventually become the National Post newsroom. We picked out the carpets and we were marking tape all over the floor to imagine where things might go.

NEWLAND: When I arrived in May or June of 1998, there was a very small team in Don Mills, which I found to be very similar to Los Alamos, the Nevada nuclear testing facility, when I first saw it. A bunker in the middle of Don Mills. I’ve always called it the nuclear testing bunker because, as with Los Alamos, there was high secrecy at the beginning, and we were trying to build something completely new that would shock people. But we came to grow fond of it. It was a bit of a roller coaster.

Advertisement 11

Article content

ANDREW COYNE, national columnist: I would have much preferred it if they’d gotten an office somewhere downtown. It was one of the small disappointments of the thing, having to commute out to Don Mills.

With an editor, space to build a newsroom, and a budget, a launch date was set: Oct. 5. Recruitment ads were placed in newspapers — featuring a mostly blank page calling for the country’s best journalists to help fill it. The Globe refused to run the ad.

LAPOINTE: The news desk that was created, people like David Walmsley, Alison Uncles, John Geiger, they were really good editors who just knew how to react quickly. They were really nimble. The push was to get the people into the place who you think are going to do amazing things. Let’s get an all-star team together: let’s get a bunch of new people who will be able to do some incredible things that will surprise us, and let’s also get some people that have great reputations and experience so that we launch as a steady ship.

WHYTE: When Martin came over, he said he wanted to bring somebody with him who knew how they operated at the Telegraph, and that’s how David Walmsley found his way over. Martin also brought Tim Rostron over, who was our first Arts editor. We also hired Alison Uncles as our national editor, Graham Parley as sports editor, John Racovali as world editor, Peter Scowen as Toronto editor.

Advertisement 12

Article content

DAVID WALMSLEY, national assignment editor: I emigrated from the U.K. on June 28, 1998. I went straight to the office in Don Mills and thought, wahey, what have we here? It was very clear, at what turned out to be four months from launch, we didn’t have that much. I think I was employee number seven. We just didn’t know what we were doing. I didn’t have a title, I was just there to do whatever I was needed for.

NEWLAND: Part of the Post’s success was its people and somehow the people who answered the call were all possessed of a degree of mischief. I’m sorry if I’m insulting people, but most people who go to journalism school have had all the mischief stamped out of them.

The Post was its people, with Ken at the top. And Ken, even though he was always impeccably dressed, very quiet, very urbane, he was one of the most mischievous people I’ve ever known. The paper’s brand was drawn from being slightly anarchic. I think that came to characterize the newsroom. Some seriously fun people came to join us, and some absolute nutbars. When the call went out, the first to respond were those who were naturally up for adventure. You had to be. It was a risk. If you get a newsroom full of people taking risks, you’re going to have a lively newsroom.

Advertisement 13

Article content

WHYTE: I don’t really remember exactly what order people came on because it was sort of a chaotic process. Isabel Vincent from the Globe was probably the first writer hired. She had been one of the earliest conversations I’d had. She was so excited about the idea she made it clear from our first conversation that if we were doing this, she was coming.

COOPERMAN: It was wild because there were so many resumés that came in. I remember some smart people wanted their resumés to stand out and would send things with them, like a cake, a huge inflatable shark. We were getting piles and piles of resumés. I remember Ken sitting in one of the cubicles with his feet up literally going through them, and we put them in huge piles with labels. There was a ‘Yes’ pile, a ‘No’ pile, a ‘Dubious’ pile — and then there was one called ‘Dubious But Young,’ because Ken was very interested in encouraging young journalists.

WHYTE: We got a lot of good intelligence from Southam editors about who they thought was the best reporting talent, and we were especially looking for the best young reporting talent because, contrary to popular belief, we had a limited budget.

CHRIS JONES, sportswriter: In the history of the world, I think I had the worst job interview ever, with Ken. I was graduating from the University of Toronto with a master’s in urban planning. I lived at Massey College and the headmaster was John Fraser, journalist emeritus. And I wrote — just for myself — and John would see me writing and asked to read some of my stuff and he set me up with an interview with Ken Whyte, who at the time was still the editor-in-chief of Saturday Night magazine.

Advertisement 14

Article content

I didn’t know anything about the newspaper. I was clueless that this was happening. Ken kept talking about a newspaper and I kept correcting him, calling it a magazine, and he said, no it’s a newspaper and I said, ‘Listen, you’re the boss, I guess if you want to call it a newspaper, it’s a newspaper.’ Later, Liza Cooperman called and said Ken was hiring a bunch of ‘unproven talent’ and we would be able to audition to work at National Post by working a summer at the Toronto bureau of Southam News. Around September people started getting plucked from the bureau to move up to the newsroom.

I interviewed with Martin Newland in news and Graham Parley in sports. I thought they were fighting over who got me. What emerged later is that they were fighting over who had to take me. There’s no rational explanation for why Ken wanted to give me a shot. He just did. I was an apprentice, essentially, so they gave me a nominal salary.

COYNE: I was a syndicated columnist with the Southam chain. When the new paper was starting up, I went for lunch with Ken and we just chatted about everything else under the sun, and then at the end as I’m getting up to leave, he says ‘So you’re gonna come on board with us.’ I look at him and say ‘I guess so.’ This maybe was in June. I was one of the earlier hires.

Advertisement 15

Article content

ROY MacGREGOR, national columnist: I was with the Ottawa Citizen, and I was very happy there. Ken Whyte came to town, and he wanted to get together and have a coffee. We did not know each other. I found him very pleasant, but I was a little reluctant to join, although it seemed exciting. The truth is, I held out and he came back with a better offer. It seemed they had money to throw around. I think I joined in September. It was a pretty magical time.

ANNE MARIE OWENS, national reporter: I was working at the St. Catharines Standard, but I was on the Massey fellowship that year. Everyone was talking about the rumours of a new national newspaper that Ken Whyte and Conrad Black were going to launch… I sent a letter, kind of cheeky letter promising all the great things I could do, and my resumé, and then I waited. I didn’t think anything would happen, but then Ken’s people reached out and I came to Don Mills.

Ken interviewed me in the cafeteria. I was so nervous about that interview. I had no air conditioning in my car, and I had to get changed in the washroom before the interview. The national news reporting team was constituted largely by reporters drawn from other Southam papers.

GLORIA GALLOWAY, national reporter: I was 40 years old. I don’t know by how much, but I was clearly the oldest national news reporter in that group of 12 or 14 who started. It was intended to be young and edgy.

Advertisement 16

Article content

There was a ‘Yes’ pile (of resumés), a ‘No’ pile, a ‘Dubious’ pile — and then there was one called ‘Dubious But Young’

Liza Cooperman

ROB ROBERTS, copy editor: I was at the Montreal Gazette and my boss there was Marv Zivitz, who came to build a copy-editing desk at the new paper. He was trying to build a desk that was both capable and collegial. Ken and Martin wanted to meet every person, so I came to Toronto for an interview. This was supposed to be the unorthodox newsroom and I tried to game out what type of questions they might ask. They asked me one question and one question only: Do you know how to use QuarkXPress? That was the publishing software they were using. I said, You bet! And I was in. The copy desk was a great mix of people, including Steve Meurice, who quarterbacked many of our front pages and went on to be a great editor-in-chief.

WALMSLEY: Each Friday, a printed piece of paper would be distributed with the staff list and their phone number. It hovered at a dozen, then 15, then 30. Construction teams came in to build a few offices.

LAPOINTE: We could barely keep track of all the people we were interviewing, and largely you ended up in an audience with Ken, or with Martin, if you were going to get hired. I wouldn’t even be able to tell you what the eventual newsroom headcount was, I think it was just over 210.

WHYTE: It was a self-selecting process. People either got the idea of going to a startup and being part of something new and maybe a little risky, or they didn’t.

Advertisement 17

Article content

COYNE: My strongest recollection was seeing all these swaggering Brits come in. Which in hindsight was really smart — these people had been in a newspaper war all their careers. The culture they brought with them, that self-confidence and sense of humour, the mix of highbrow and low brow. Ken brought a lot of impishness and intellectual curiosity; there was a mixture of influences.

LAPOINTE: We did a pretty brisk business in getting people working visas.

WHYTE: Christie Blatchford came on board after a loooong torturous recruitment. I probably worked harder on her than just about anybody. Christie was our number one target because in our research, it was clear that a lot of columnists had name recognition but there weren’t very many who meant so much to readers that they would change their newspaper allegiance if that columnist moved to another paper. She was one who had that kind of loyalty. Terry Corcoran, from the Globe’s Report on Business, was one of the first that we asked and one of the last to say yes.

FISHER: I got involved with two important people. One was Christie Blatchford, the other was Terry Corcoran. Christie asked me if this was really going to go forward. I did my best to assure her. Ken probably had 10 to 12 dinners, drinks, meetings with Christie. Terry had a similar view: he wanted to know the commitment Mr. Black had. I went to Conrad and said, ‘Are you interested in Terry Corcoran,’ and he said he was very interested. Terry didn’t come cheap; neither of them did. It became my job to figure out how we were going to pay everyone.

Advertisement 18

Article content

The paper still had no name. Southam had applied to trademark more than 15 possibilities, according to the trademark registry. Leading contenders used on prototypes were Times Canada, The Canadian, and The Times. Other applications included Newsday Canada, Nation Today, Canadian Times, National Times, Daily Nation, New Canadian. On April 27, 1998, another contender was submitted for trademark: National Post.

FISHER: We did that to protect ourselves because at the same time, the Globe was trademarking titles knowing that we would be looking for one, so they were trying to block us.

BABICK: We struggled, mightily, finding a name for it.

We got the frontpage story count to a minimum of seven — seven stories on the front page, every day — in order to hook as many people as possible

Ken Whyte

FISHER: We had various names. I think the one we took forward with our first mock-ups was The National, but we also recognized that was problematic because CBC had a flagship news show called The National.

WHYTE: We kept going back and forth on names. There were literally dozens of contenders including some that were way out there. There were so many ideas floating around, it was driving us all crazy.

KELLY McPARLAND, deputy world editor: I still remember the total chaos of the first weeks and months. No one knew the policies on anything. If you had to miss a day, no one knew who to notify. No one knew where the notepads were kept. Since everyone was new, no one knew who was in charge of what. You just turned up and hoped they remembered you from the day before.

Advertisement 19

Article content

WALMSLEY: One day, in early July, Mark Stevenson and I decided to draw up some pages of what a design could look like. Except we hadn’t any pencils. The superb design team that made the Post what it remains today came on board not a moment too soon.

WHYTE: One of the things which I thought was really important to the success of the Post was the design. Both on the front page and inside the newspaper. Front pages tended to be down to about three or four stories at most newspapers, but we wanted a real sense of dynamism, so we got the frontpage story count to a minimum of seven — seven stories on the front page, every day — in order to hook as many people as possible. There were a number of people involved in the design, Lucie Lacava, Gayle Grin, Leanne Shapton.

GAYLE GRIN, design director: It was a thrill to design something from nothing: a startup, something with no legacy. The team creating the design — Lucie Lacava, design consultant, and design directors Roland Yves Carignan and myself — created the design out of nothing, a rare experience.

NEWLAND: Journalism was so unbelievably boring then, especially in North America. The National Post’s first mission was to completely obliterate the earnestness of North American journalism and to follow news for the news’s sake, rather than because it fit a template of public service. This was Ken’s paper. Ken was the iconoclast. Ken was the one with this deep sense of humour. Ken was the one with the fuck-em-all attitude. I was his very effective enforcer, shall we say.

Advertisement 20

Article content

News is about play. It can be funny, it can be shocking. A national newspaper is not just established by reporting national institutions. A national newspaper is also established by making someone on one end of the country feel the same emotion as someone at the other end. It’s a kinship of emotion and reaction and often those reactions are to fear, humour, and the spectacle: sport is a great one. If you can evince the same emotion from someone at the outer edges of B.C. as someone in Toronto through telling a story, you are establishing a national connection.

OWENS: As national reporters, we called that summer before launch the Summer of Love. We were all people who didn’t really know each other, put together for this common mission, and they wanted us to get to know each other and to bond, which often meant drinks and dinners. At the very beginning there were no hard deadlines, the pace was leisurely for us before we got to the launch. Except for when we were doing dry runs.

BABICK: We did about two weeks of dry runs — creating editions of the National Post that never hit the streets.

GALLOWAY: It was about proving that when the pedal hit the metal, we could actually put a paper out in a day. It’s a complicated process putting out any newspaper, but we had all kinds of people who had never done this before.

Advertisement 21

Article content

The National Post’s first mission was to completely obliterate the earnestness of North American journalism

Martin Newland

WHYTE: I remember those days fondly. It was a lot of fun doing the practice runs.

GRIN: Good thing we had dry runs. Funny and frustrating time. Stories came in too long, stories would come in late. The design created was counterintuitive and not easy to learn. A lot of time was spent training copy editors how to manoeuvre design libraries, access templates, and giving feedback on practise page designs. Around the clock adrenaline leading to the launch.

OWENS: We went out and reported things. ‘Hi, I’m working on a story for the new newspaper that’s going to launch.’ They would say ‘What’s it called?’ ‘Oh it doesn’t have a name.’ ‘When will this story be published?’ ‘I’m not sure it ever will be.’ It’s kind of remarkable how many people did talk to us.

FISHER: Meanwhile, we had some concerns. We were going into our markets and holding focus groups and showing prototypes of our newspaper ideas, to get a reaction to it from the desired demographic we were hoping to attract. And, generally they were positive, but there were two things that leapt out every time: one was the financial section isn’t good enough, and sports was a bit of a concern.

LAPOINTE: Then came the July blockbuster.

On July 20, 1998, two of Canada’s largest newspaper chains announced a surprise deal: Southam swapped four Ontario newspapers, including the Hamilton Spectator and Waterloo Record, plus $150 million, to Sun Media in return for the Financial Post, a Toronto-based business daily.

Advertisement 22

Article content

Article content

JOHN IVISON, deputy business editor: I had been deputy business editor at Scotland on Sunday in Edinburgh and was hired to be the deputy business editor for a new finance section. As we were coming in from the Toronto airport, over the taxi cab radio we heard the announcement that Conrad Black had bought the Financial Post. I’m thinking: Do I still have a job here? My God, there’s going to be somebody waiting to say the deal’s off. All our stuff is already en route across the Atlantic. So, it was a nervous start.

FISHER: It came as a surprise even to me. Don called me on the weekend and said, ‘I’m going to rock your world,’ then said that on Monday we’ll be announcing a deal to buy the Financial Post. David Radler negotiated the deal.

We had to go down to the Financial Post building after the announcement and introduce ourselves. Earlier in the day, Bill Neill, who was its publisher, had told staff it won’t change much, it’s still going to be a tabloid, still a standalone newspaper, and then later that afternoon, Don Babick had to explain to them, well, no, we were actually going to incorporate it within the new newspaper, and it would become a broadsheet. There was a lot of drama that day.

IVISON: The people who had been hired to start a business section would essentially now run the new iteration of Financial Post. Ken sat us down — Howard Intrator, me, Michael Den Tandt — and said, turn this tabloid into a business section. When the FP staff came up to Don Mills it was tense. They were not happy.

Advertisement 23

Article content

BARBARA SHECTER, Financial Post reporter: I remember heading uptown to the newsroom in the leafy Toronto suburb of Don Mills after the tabloid Financial Post was acquired… We’d lost a few key people along the way, which was unnerving, but reunited with others, including our smart and dedicated leader, Howard Intrator, who’d been hired earlier, handpicked by Ken.

I think both of us felt, Thank Christ Conrad bought this thing because otherwise we were never going to solve the name debate

Ken Whyte

Our days were filled with filing two versions of every story: a short one in the style of the tabloid we were leaving behind but still publishing daily, and a much longer narrative to be edited and placed in the mock newspaper we were producing to be ready for the launch of the National Post.

Buying the Financial Post not only resolved the need for stronger business content, it solved another nagging problem.

WHYTE: I remember talking to Gordon Fisher just after the Financial Post purchase and he asked me ‘What do you think about a name now?’ and he and I both agreed that National Post was the obvious name and really the only one that made sense. I think both of us felt, Thank Christ Conrad bought this thing because otherwise we were never going to solve the name debate.

BABICK: It made it easy, because when we bought the Financial Post, we had a fine name that belonged to us. We tried all these other names on people in the focus groups; some of them didn’t fit well, some sounded like they were government publications. Nobody jumped for joy at any of them.

Advertisement 24

Article content

COYNE: I wanted them to call it The Canadian. I was a little disappointed when they chose National Post.

COOPERMAN: The closer we got to launch, the harder we worked. We worked all the time. There was all this energy around it, it quickly became super exciting.

WALMSLEY: Humour was essential as the hours were extraordinary. Eighty-hour weeks were the norm, and we didn’t care. It was a privilege and a mission. The Friday drink cart supplied an end of week hint of celebration. The rule was simple: Drink as much as you want. Just don’t make a mistake.

DOUG KELLY, FP Investing editor: We commandeered the mail cart as a drinks trolley and served themed drinks to reporters as deadline approached. What could go wrong?

WHYTE: I don’t recall exactly how Friday Drinks started. I just remember that it was informal; part of the newsroom got a delivery that included some alcohol and so they brought it over and shared it.

BABICK: (Friday Drinks) was interesting. I remember Ken telling me he wanted to do this and I was ‘Oooh, this could be an issue.’ But, you know, it worked out and everybody came and it was just part of the routine after a while.

WALMSELY: In time, each department took responsibility for hosting a themed drink. It became competitive.

Advertisement 25

Article content

ROBERTS: To me, that was the kind of unexpected joy of Friday Drinks. You never knew what was going to happen. Toronto mayor Mel Lastman came in to serve us Toronto beer; I remember Team Canada goaltender Sami Jo Small came with her Olympic gold medal. The first album I ever bought as a kid was a Triumph album, so a chance to meet Rik Emmett in person in our office, unbelievable.

Article content

COOPERMAN: I was the keeper of the filing cabinet full of booze. Friday Drinks evolved into something where we assigned different departments to do it and then everybody was trying to one-up each other. One department brought in exotic reptiles, and they put a huge python around a reporter’s shoulders, and it kept trying to wrap around his privates. It was very awkward.

We had a mariachi band; we had the Raptor mascot come. We had a lion once. It was absurd, it was really crazy.

WHYTE: I had a good ping pong match with the Raptor. He was surprisingly good. The ping pong table in the newsroom was just for fun and to keep things a little lighter and less formal. We had our editorial meetings around the ping pong table.

The launch date was pushed back to Oct. 27, 1998 — a Tuesday. The Saturday before, a huge launch party was held at News Theatre on The Esplanade in Toronto. More a glamourous ball than a normal newspaper party, it was attended by 300 people and TV news crews lined the red carpet leading to the entrance. The catering bill was $13,980.

Advertisement 26

Article content

IVISON: I walked in and there’s massive ice sculptures all over the place and people handing me free drinks, and it had a sense that we were in another world, where the laws of economics did not apply.

GALLOWAY: It was glamourous. To me there was a glamour to the Post that I’ve never felt before or since, kind of feeling like we’re doing things in a very upscale way.

NEWLAND: It was very posh, wasn’t it.

MacGREGOR: Conrad and Barbara Amiel (Black’s wife) just floated around the floor saying hello to everyone and were like royalty.

SCOTT MANIQUET, library technician: At that big party for the launch, Barbara Amiel was going around saying hello to everyone and she came up to me and asked who I was and where I worked and then asked if we needed anything. I said we need more staff in the newsroom library. On Monday, the Financial Post editor announced we had to find someone new for the library. Which is insane.

Monday, Oct. 26, was spent creating the next day’s newspaper, National Post’s launch edition. It was an early start and went late. Correspondents across Canada and around the world filed stories and photos to the Don Mills newsroom, where it was all-hands-on-deck.

WHYTE: It’s one thing to conceive of a national newspaper and then another thing to actually see it come out.

LAPOINTE: I think it was a crazy good launch. It was a stunning number of people collaborating in order to produce one product. There was a minimum, in a lot of ways, of chaos about it. It could have been way more chaotic.

ROB McKENZIE, senior copy editor: Many of us had a genuine passion for the paper. We wanted to win. We believed newspapers should be a pleasure and not just a duty. We wanted to challenge the established order. This was our chance to be part of something great.

As the day built you could feel that newsroom energy — I miss it to this day — that buzz as the day goes on and phones started ringing more and people are running in and typing and shouting

Chris Jones

COOPERMAN: Do you remember the National Post leather jackets on the morning of launch? We put them on everybody’s chair — I probably did — put them on everybody’s chair the day of launch. I think Kirk LaPointe got in huge trouble for that after for the expenditure.

LAPOINTE: The mistake we made was that we’re only doing it for the newsroom and word got around in the executive ranks that the newsroom was going to do it but nobody else, so it became a thing. Gord was upset because Ken and I hadn’t gone to him to get the money approved for the jackets. Basically, they ended up getting them for everybody.

FISHER: In hindsight, maybe we shouldn’t have been so annoyed. It was a small amount of money relative to what we were really spending. I love my leather jacket, I gotta say.

JONES: I remember coming into work early. As the day built you could feel that newsroom energy — I miss it to this day — that buzz as the day goes on and phones started ringing more and people are running in and typing and shouting; the feel of that room building to this crescendo that is deadline. I remember watching the place just explode that night. I was so excited to be there. I wanted to get in that first paper so badly but because I didn’t have a real role, there wasn’t anything for me to do. Then Graham threw me a bone and he asked me to rewrite a piece of wire copy about a kid who had been cut by a skate in Newfoundland. It was Graham’s way of making sure I got in the paper, and it was a lovely gesture.

OWENS: We were all desperate — I’m sure every department was the same: Is my story going to make it into the first edition?

SHECTER: What I recall most, particularly for the younger journalists among us, were the nerves and sense of competition, not only with our crosstown rivals at the Globe. but within the newsroom itself — we all wanted to carve out a place in the history being made.

IVISON: Marvin Zivitz was on us to meet deadlines. Marv added a degree of professionalism to make it a proper newspaper: the style book, for example, the fact that we had to correct stuff. He provided a degree of adult supervision — part of the magic of it was that it required adult supervision.

FISHER: The newsroom was going nuts but I’m watching the guys in IT as page flow starts to build. It’s their job to get these pages to various printing plants around the country. It’s something we’ve never done before. There was huge tension around that.

Conrad had made it clear that he and Barbara wanted to be in the Sun building in downtown Toronto when the first copy of the Financial Post section was printed there. The Hamilton plant was printing the other sections, then we trucked all of the other sections to Toronto. That was not a sophisticated operation; it was a bunch of guys in a room stuffing the various sections together by hand. It was totally chaotic.

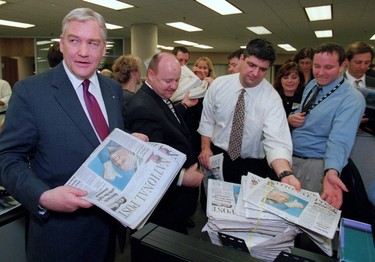

There were hitches at the Toronto plant. They kept having false starts and kept having to rewind the presses. Pat Brennan (in charge of print operations) was just a nervous wreck. There were cameramen there and eventually Conrad clambered down steel steps covered in grease and was photographed standing on the press deck holding the first copy of the new Financial Post. Then we all got in our cars and headed up to the newsroom.

COOPERMAN: As the pages were put together, we had printouts of the pages lined up on the floor of the newsroom. Conrad and Barbara were walking around and there was a crazy buzz. It was amazing.

BABICK: Conrad, Barbara, and a bunch of us stood around the Post newsroom at midnight still waiting to see the first copy of this new national newspaper. My daughter, who lived in Calgary, phoned me around 10 o’clock and said ‘Dad, the paper looks spectacular.’ She already had a copy of the National Post there. It was a long night.

NEWLAND: I remember I had to put on a suit for the first time in three years. I didn’t take well to suits, at all. And I remember the stately progress of Conrad and Barbara through the newsroom.

FISHER: Dennis Skulsky arrived from the press room with bundles of the fully packaged newspapers. All of us — Conrad, myself, Don, Ken, all the journalists, everybody in the room — finally got to see the first edition of the newspaper for the first time. So that was a great moment, and we popped some champagne.

NEWLAND: I remember just being terribly tired. Launching the paper, sometimes we’d go two days without sleep at all.

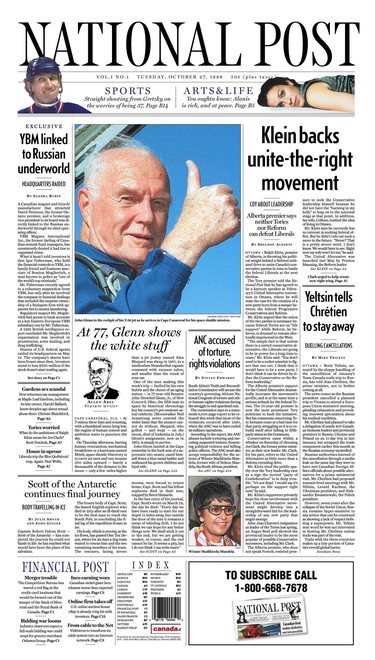

BLACK: We were up at the editorial office in Don Mills, in the newsroom, when it came in. I was sort of surprised that the (front page) picture was of John Glenn, the astronaut… ideally it would have been a Canadian person, but it was a perfectly justifiable thing on the news of the day. I thought it was lively, caught your attention, and held your attention going through it. It was a nice atmosphere, and we were all sitting there reading the paper until about 3 a.m.

JONES: I remember running to the newspaper box the next day to get it and it was hard to find. I remember going to several boxes and I couldn’t get a copy. I finally got one. I still have it.

FISHER: I think we printed about 500,000 copies and they were snapped up. The newspaper boxes, our swanky new boxes that were all over the cities, were cleaned out immediately. We were getting calls from vendors saying they needed more newspapers, so it was a truly great day.

LAPOINTE: Everybody was totally applied to the idea that we were going to be as elegant as we could be in those circumstances; so the writing was fantastic and there was gifted photographers, the design work was really worked upon and worked upon, and the result was some of the best newspapering that the country has seen. We felt a creative freedom to do the best possible work and not consult the finance department.

WHYTE: It didn’t look like other papers, it didn’t read like other papers.

BLACK: I think some people were expecting us to be sort of extreme and strident.

MacGREGOR: It was a hell of a paper.

COYNE: There was a period there where, for the first and perhaps only time in his life, Conrad Black was cool.

WHYTE: We get the thing off the ground and circulation starts to build but there aren’t a lot of advertisers. It was, like, 48 blank pages that we were filling every day. It was a lot of space.

IVISON: I remember every morning waking up thinking how the hell are we going to fill this today. It really was a daily miracle.

McKENZIE: The biggest difference from my prior job at the Globe and Mail was that when you had an idea at the Post, they would use it — if it was a good idea. This lack of internal walls was a powerful force in our favour.

NEWLAND: I think the news meetings were the most fun anyone ever had. Some of the stuff that was said there, I mean, they’d have people behind bars, now. Peter Scowen would just go off on some sort of stand-up comedy bit. Graham Parley, God broke the mold after he emerged. Ken would sit there in silence, perhaps ask one or two questions, and at the end of everyone doing their riffs and pitches, would pick with utmost perfection the stories that were going to make the difference.

JONES: The sports department was a special collection of people. I remember watching Cam Cole, just watching him work. Cam was such a great example for me to see at a young age.

OWENS: Though we were competitive, we were more collegial than we were competitive. Not quite sure how that magic happened. There were no beats for national reporters. We came from different regions and most of us had worked for local papers, where we were rooted in a place and our stories were rooted in a place. And all of a sudden, the entire country was our playground, not even just our country, it was the world.

GALLOWAY: I had done a short story on Canadian researchers planning to go to the Gobi Desert to watch the Leonid meteor shower, which was supposed to be specifically fantastic there in 1998, and an editor said, ‘Boy, you have to and go watch this.’ I said, ‘You want me to go to the middle of the Gobi Desert and try to file a story for a daily newspaper when I have no idea how or when I’m going to get that information back to you?’ And they went ‘Yeah yeah, you have to go.’

The runway in Ulan Bator was completely covered in snow, they had to get guys with shovels to shovel it off before the plane could land, so I was really late getting in. I got there just as the expedition was taking off into the snow-covered desert to this old, abandoned Russian observatory, with the former head of Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars program. It was like -40 degrees outside. The Globe and Mail knew we were doing this; they were concerned about the competition and so they sent poor Miro Cernetig there to join us.

It was too cold to stay outside, so we would run out and look up at the sky and run back in. And maybe we saw a meteor, maybe saw two. It was a perfectly clear night but somewhere along the line astronomers decided they made a miscalculation, and it would have been better to see it in California. I wrote a story, yeah, although there wasn’t much to say. It ran because they’d spent all this money to send me.

One of the great things that the Post did, it really did shake things up in terms of opportunity in Canadian journalism

Ken Whyte

FISHER: Conrad’s belief was that if we were to produce a newspaper that was as good as we thought it would be and as extensively distributed as we knew it would be, then advertisers would come flocking. We had toured all the ad agencies numerous times to show them prototypes and try to get them excited. We were hearing that wasn’t necessarily going to happen as easily as we would like it to. It was a big concern.

BABICK: I had more than some concerns about money, and Ken Whyte and I had chats about that, and later with Doug Kelly, who became executive editor. There was a lot of back-and-forth conversations about the size and amount of money we were spending. You have to rationalize two things: we had one shot of making this a great newspaper that was going to catch hold, and to do it, we knew it was going to cost money. Were there things I thought that we overspent on, that were frivolous? Absolutely.

The editorial budget of National Post in 2000 was $29 million; newsroom expenditures that year totalled $30 million, according to internal documents. Overall, the Post brought in $150 million in revenue on $180 million in expenses that year.

OWENS: We worked all the time. All the time. Really long hours. We had so much space to fill. We would pitch a story to be working on that day and you think it’s to be 600 words, and then late in the afternoon an editor would say ‘We decided your story is going to be the Reporter page’ — that’s page three, the big storytelling page that eats a full page. It’s great for you as a journalist but it means it goes from being a 600-word story to a 2,000-word story with not a lot of time to do it. It was: Make it good, make it fit, but also write it really fuckin’ fast.

You weren’t on your own when that happened because it was going to happen to each one of us, and it did happen to each one of us, so other reporters jumped in to help. Then you’d reach out to the newsroom library and say, tell me everything you can about the geography of the area.

MANIQUET: The internet was pretty new and not many people were doing their own database searches, so they would ask us to do that. We had access to a lot of information.

FISHER: That first year was one of growing confidence and excitement around what we were doing. The paper got better as the days and weeks went on.

GRIN: A few months after launch we were recognized internationally with design awards. We won our first ‘Best Designed Newspaper in the World’ from the international Society for News Design.

Two months after launch, a published profile of musician Alannah Myles led to a $9 million defamation lawsuit against the Post. It was settled out of court but sparked a push for greater rigour in newsroom policies and procedures.

WHYTE: One of the great things that the Post did, it really did shake things up in terms of opportunity in Canadian journalism. We came in and found huge numbers of really talented young people who we essentially gave them their first jobs. And because we were hiring, other newspapers started hiring, and talent became a little more important — a lot more important, in fact — than it had been for generations in Canadian newspapers. It’s amazing what just one addition to the competitive pool can do for the whole environment.

Article content

McKENZIE: The Post was the funnest job I ever had.

BABICK: I might have done some things differently if I was doing it over again, but I thought it was one of the highlights of my career, being the first publisher and the founding publisher.

NEWLAND: There was that wonderful sort of anarchic sense around it. I do miss those days, I have to say. Professionally those were the best years of my life. It’s the only time in my professional life I look back on — and you know I’m not the sort — and get just a little bit misty.

BLACK: I think its durability has surprised people.

ROBERTS: Understanding and executing the idea of the Post has been a key mission and I think maybe the people who were there on Day One have been uniquely qualified to understand the vision. When Ken Whyte left, there was a brief interregnum with a non-Postie that didn’t go that well. Doug Kelly, who’d been there in the beginning, replaced him as editor and, when Doug became publisher, Steve Meurice, who’d been there on Day One, took over, and when Steve stepped aside, Anne Marie Owens, who’d been there on Day One, took over. When Anne Marie left, I had that special honour. I knew the importance of the Post being the Post.

WHYTE: There was always something fun in every issue, which I think the Post has done a remarkable job of carrying on that tradition. It is still, in Canada, by far the most enjoyable paper to read. It’s got a sense of humour about itself and about the world and a lightness to it without being frivolous. It knows how to laugh and it knows how to entertain its readers. I think that’s always been a strength and it’s a terrific thing that carries on to this day.

Adrian Humphreys is a Day One National Post reporter.

• Email: ahumphreys@postmedia.com

Article content