Regular passengers of the “Tombouctou”, a ferry whose route runs along the Niger River in northern Mali, are accustomed to hearing gunfire from the riverbank during their journeys.

But on September 7, they quickly realised that something unusual was happening.

The blasts that forced passengers to hit the deck that day heralded a deluge of gunfire.

It would destroy dozens of lives and leave the ferry — which provided a regular link between Malian towns on the banks of the river across hundreds of kilometres of semi-desert — a burnt-out wreck.

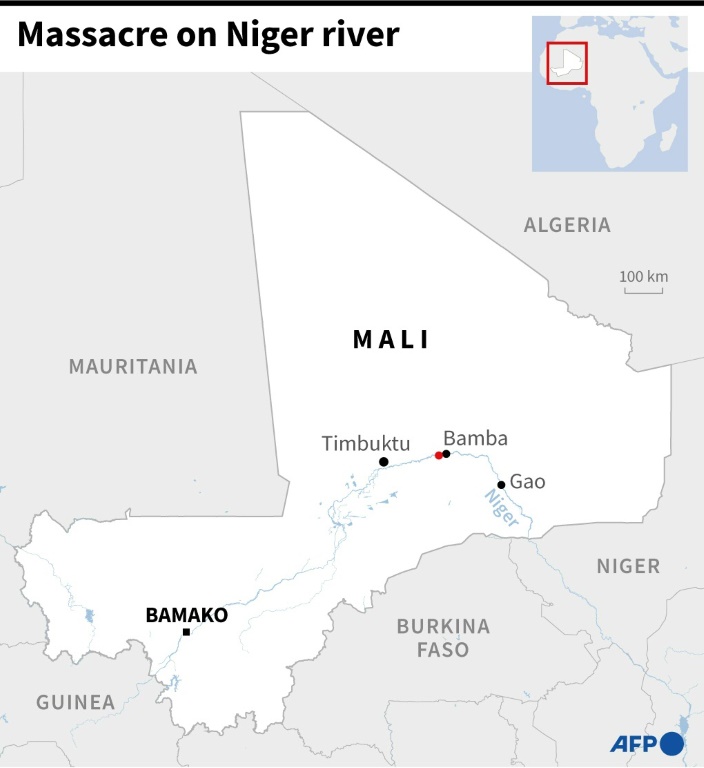

Even in a country accustomed to massacres attributed variously to jihadists, self-defence militias, the army or, more recently, the Russian paramilitary group Wagner, the carnage committed some 20 kilometres (12 miles) upstream from the town of Bamba stands out — and not just for its scale.

Nobody really knows who unleashed the 15-minute inferno of rockets, bullets and flames on hundreds of passengers, and there is no guarantee that the truth will ever be established.

Twelve witnesses agreed to recount the events to AFP. They described the terror, but also the sacrifice of the soldiers and the solidarity between the victims.

Since 2012, the Sahel has been the scene of countless atrocities that often go unreported and without photographic evidence.

These accounts add an element of humanity to what would otherwise be just another faceless massacre.

One of these witnesses, Alhadj M’bara, described himself as a veteran of the “Tombouctou” — the white and blue three-decker boat with a slightly old-fashioned but dashing flag bearing the logo of the Societe Malienne de Navigation (Comanav).

M’bara, who is in his sixties, sat on a mat in his old walled house in the city of Timbuktu as he recounted his story.

He said that, like others, he used to sell small household items on the boat during its multi-day journey.

He had his regular spot on deck, which is where he was at dawn on September 7.

Between 500 and 1,000 people were crammed on board, although the ferry was only designed to carry 300.

It was almost breakfast time, and the passengers were worried.

“Since we left Timbuktu, we had heard rumours that the boat would be attacked,” the old man said.

For weeks, the situation had been escalating between armed actors in the north, including jihadists, separatists and soldiers.

The Al-Qaeda-linked Support Group for Islam and Muslims (GSIM) had imposed a blockade on Timbuktu, and anything travelling to or from the city became a potential target.

Before the attack, the river had offered a generally safer alternative to the road.

On September 1, however, a teenager was killed by a rocket attack on a Comanav building.

Five days later, the occupants of a boat passing the Timbuktu ferry from the direction of Gao warned passengers of a threat lurking.

As a precaution, a stopover was arranged for the night at Bamba, between the cities of Gao and Timbuktu.

At around 9:00 am (0900 GMT) the next day, some 15 kilometres after Bamba, the ferry entered a bend lined with reeds.

Aicha Traore, a student, was taking photos on the bridge when one or more pick-up trucks, according to witnesses, appeared over the dunes on the horizon.

“Some people whispered that maybe it’s the village chief’s car,” she said.

There were soldiers on board the boat, and she and others went down to inform them.

The question has been raised whether the soldiers’ presence made the ferry a target — and, if so, for whom.

“That’s when the shooting started,” said M’bara, the salesman.

Soldiers ordered people to lie down on the deck.

“Some of them lay on top of us to protect us,” recalled Abdoul Razak Maiga, a 19-year-old student.

The Timbuktu ferry has come under fire before, according to M’bara.

But “this time it was different”, he said.

“We were ashore (when) suddenly a rocket came out of one of the pinasses,” the small flat-bottomed boats that abound on the river, some of which were following the ferry from Bamba.

“From then on, it was every man for himself, God for all,” M’bara said.

The soldiers tried to retaliate, but were caught in the crossfire of small arms and rockets.

Three rockets hit the engine, the ferry operator said.

They started a fire that spread.

“I gave my little brother to someone while I threw myself into the water,” said Fatoumata Coulibaly, a shopkeeper.

“Then I signalled to him to throw me my little brother — I was able to swim to shore with him (but) all our luggage remained, even our clothes and shoes.”

In the panic, Aessata Issa Cisse, another passenger, was separated from her daughter.

“I’ve had no news of her — I’ve searched in vain, I don’t know if she’s alive or dead,” she told AFP.

The captain managed to reach the shore.

Local villagers were the first to come to the aid of the survivors.

A few hours later, soldiers and around 15 armed white men, possibly mercenaries from the Wagner Group, arrived.

The attackers had vanished, but the road was too dangerous to evacuate the survivors, who spent the night under military guard in front of the burning wreckage.

The dead were buried on the spot.

The number of casualties is unknown. Access to such data is hampered by a multitude of factors: the remoteness and perilous nature of the terrain, the shortcomings of telecommunications, the paucity of information relays, and also a fear of speaking out.

Massacres in the region have often been documented for NGOs and the UN based on oral testimonies.

Access has become even more limited in recent years, in a tense security and political context.

Yet news of the ferry massacre spread in a matter of hours, with images of the boat in flames circulating on social networks.

Mali’s ruling junta, often slow or reluctant to speak out in such circumstances, addressed the incident publicly that same evening.

It confirmed the deaths of 49 civilians and 15 soldiers in the ferry attack and another on the same day against army positions in Bamba.

The junta said that GSIM had claimed responsibility for both operations. AFP only found traces of the group claiming responsibility for the attack on army positions, but not for the ferry.

Subsequently, authorities lumped the assault together with other acts by “terrorist” groups, a term they now apply to the separatist fighters who have just taken up arms against the state in the north.

Pro-junta groups active on social networks openly blame the predominantly Tuareg rebellion for the ferry tragedy, compounding it with GSIM.

“Renewed tension in the north — the coalition of terrorists and independence fighters at work,” ran the headline in the government daily newspaper l’Essor on September 11.

An official from the Coordination of Azawad Movements (CMA) — the main alliance of separatist groups — has denied any involvement, speaking on condition of anonymity so as not to appear to grant credibility to the claims.

As is often the case, eyewitness accounts also invalidate the official death toll.

Several survivors say that 111 dead were buried in three separate graves for men, women and children.

This does not include those who were burnt or drowned, they said.

No information is available on the identification of the victims, or whether any have been identified at all.

The ruling junta decreed three days of national mourning.

It cancelled festivities scheduled to mark Mali’s independence on September 22 and ordered the celebration money be donated to the victims.

Witnesses confirmed that they had received compensation of 250,000 CFA francs (about $400).

The courts announced an investigation and the head of the junta, Assimi Goita, assured that this attack and others “will not go unpunished”.

Despite suspicions, the perpetrators have not yet been identified. None of the witnesses have commented on who they might be.

The day after the tragedy, in the late afternoon, small boats took the survivors — about 400 people — to the town of Gourma-Rharous, a few dozen kilometres upstream.

There they waited in classrooms for several days before being taken home.

Traore, the student, remembered the screams of the traumatised survivors at night.

She said she is the only survivor from her cabin.

“What has happened to us is God’s will,” she said with a sombre look in her eyes but a firm voice, sitting in her mud house in the city of Timbuktu.

M’bara, who saved his son by grabbing his hand and pulling him into the water, hoped that the river traffic would resume.

“Staying idle is not the solution,” he said.