Yelena Efros has been sending letters to Russian prisons for years, as the head of a volunteer group writing regular dispatches to the country’s swelling ranks of political prisoners.

But six months ago, she found herself staring down at a note she never imagined writing — a letter to her daughter, jailed over an award-winning play she directed in 2020.

Russian authorities arrested Efros’s daughter, director and playwright Yevgenia Berkovich, in May on charges of “justifying terrorism”.

The offence is punishable by up to seven years in prison.

“If they were going to lock anyone up, I thought it would be me for those letters,” Efros, 64, told AFP.

The case against Berkovich, 38, and fellow playwright Svetlana Petriychuk, 43, stems from their play about Russian women who were recruited into the Islamic State (IS) group and travel to Syria to marry IS fighters before returning to Russia.

Titled, “Finist, the Brave Falcon” after a Russian folk tale, it received two prestigious “Golden Mask” awards in Russia.

But critical acclaim has counted for little since Moscow accelerated its campaign against artists and cultural figures amid its military offensive on Ukraine.

Actors, directors, writers and performers have seen their work censored, been fired, forced into exile, or arrested.

Rights groups say the case against Berkovich and Petriychuk is particularly controversial.

The charges stem from a linguistic analysis of the play using a fringe research method into extremism and terrorism called “destructology”.

Dismissed as pseudoscience by its critics, an analysis based on its approach found the play promoted Islamic State and advanced “radical feminism”.

Lawyers have dismissed the idea as absurd.

A justice ministry agency has also rejected that initial interpretation, and prosecutors are seeking to keep both Berkovich and Petriychuk in jail while a new study is completed.

Far from “justifying terrorism”, the play is an obvious criticism of the Islamic State and a cautionary tale about young Russian Muslim women recruited to join its ranks, Berkovich and her supporters argue.

Last week, Efros travelled from her home in Saint Petersburg to Moscow for a court hearing on extending her daughter’s pre-trial detention.

Around 20 of Berkovich’s supporters also came, some chanting “we love you” as she was taken into the court in handcuffs.

Berkovich urged the judge to let her return home to her two adopted daughters while she awaits trial.

“Two sick children were taken from their mother six months ago… It’s torture,” she said.

Berkovich adopted the two girls, now in their late teens, four years ago after they had spent most of their lives cycling through Russian orphanages and foster homes.

Her younger daughter has recently started having nightmares where she sees her mother dying in prison, a psychologist told the court.

The prosecutors, who appeared unmoved by the testimony, welcomed the court’s ruling to extend pre-trial detention until January 10.

“Happy New Year,” Berkovich shouted from a glass cage in the court after the judge read the ruling.

Before being whisked back to jail, Efros approached the glass cage where Berkovich was being held and placed her hand against her daughter’s on the other side.

The pair exchanged a “Meow” — the family’s codeword for affection, stemming from their shared love of cats.

“The judge has no conscience, no power, they are just acting out a pre-planned program,” Efros said outside the chamber.

Berkovich’s lawyer Ksenia Karpinskaya said she could not understand “such cruelty”.

Berkovich comes from a storied family of activists on both sides.

Efros’ mother, Nina Katerli was a writer who fought for human rights and against anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union and 1990s.

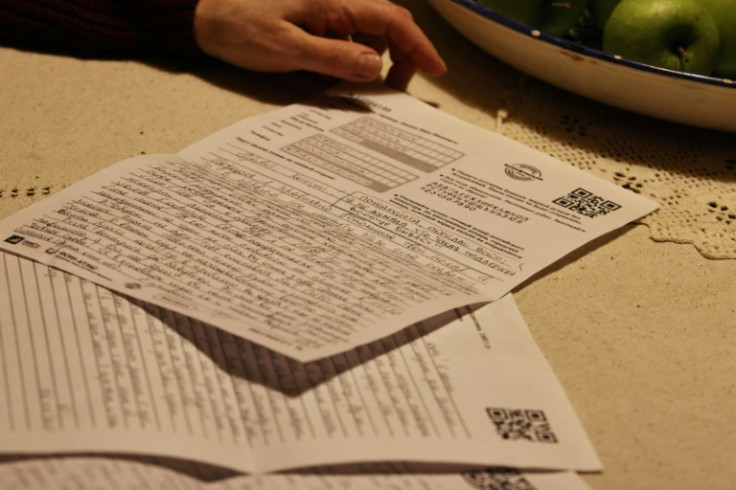

After the hearing and before boarding an overnight train back to Saint Petersburg, Efros shared some of the letters the pair have been sending to each other with AFP.

In them, Berkovich gently teases her mother over a sitcom she’s started watching.

They never say they love each other — “it’s not our way,” Efros noted — instead using pet nicknames, soft-sounding derivatives of “kot”, the Russian word for cat.

The case against her daughter is a sign of Russia targeting “free women” — those who refuse to “know their place is in the kitchen,” Efros said.

“Toxic masculinity” has flourished in Russia since February 24, 2022, when Moscow sent its troops into Ukraine, she said.

“Our country is heading towards a traditional archaic society — a Domostroy — where feminism is of course evil,” Efros said, referring to a sixteenth-century domestic Russian code that encouraged men to hit their wives and children.

She sees parallels between this trend and the play Berkovich is being punished for.

“It’s a kind of fundamentalism — it could be Islamic fundamentalism, but it doesn’t have to be, it can be Orthodox fundamentalism, or just simple fundamentalism,” she said.

“Radical feminism, from the point of view of these people, is evil.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP