Madagascar voted in highly contested presidential elections Thursday that were boycotted by most opposition candidates, resulting in a low turnout.

After polling stations closed and counting started, the electoral commission, which the opposition accuses of lacking impartiality, estimated 39 percent of the 11 million people who were registered to vote did so.

Two senior sources at the electoral commission speaking to AFP on condition of anonymity, had put the figure at less than 20 percent.

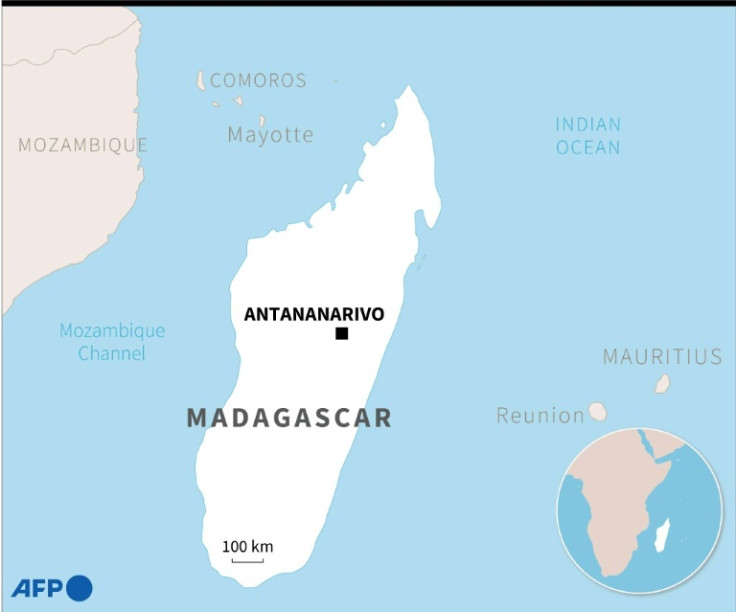

President Andry Rajoelina has voiced confidence in being re-elected, brushing off weeks of protests that have rocked the Indian Ocean island nation.

But most opposition candidates disowned the vote.

“We do not recognise these elections and the Malagasy population in its great majority does not recognise them either,” Hajo Andrianainarivelo, 56, told a press conference in the capital Antananarivo, speaking on behalf of 10 of 12 opposition candidates.

“The elections did not respect the required democratic standards and this was proven by the participation rate, which was the lowest in Madagascar’s electoral history.”

The opposition grouping had urged voters to shun the ballot, complaining of an “institutional coup” in favour of Rajoelina, 49.

“There are always people trying to stir up trouble and prevent elections in Madagascar,” Rajoelina said after voting in Antananarivo.

“I’m confident in the maturity of Malagasy democracy, and I’m also confident in the choice of the Malagasy people.”

A poor turnout is likely to strengthen the opposition, which has vowed to continue protesting until a fair election is held.

Turnout in the first round of the last elections in 2018 was about 55 percent.

Voting passed off calmly in the capital, AFP journalists saw, with voters emerging from rudimentary polling centres, their thumbs stained with green and gold indelible ink.

“I’m voting, but we know this isn’t normal,” said 43-year-old Eugene Rakatomalala. “There weren’t any candidates who did campaigns.”

Madagascar is the leading global producer of vanilla but also one of the world’s poorest countries and has been shaken by successive crises since independence from France in 1960.

“We have to move on, turn the page. For 60 years that was already the case, and I think we have to stop now,” computer science student Francky Randriananantoandro told AFP.

From October, the opposition grouping, including two former presidents, has led near-daily, largely unauthorised protest marches.

Police have regularly dispersed them, firing tear gas.

Rajoelina first took power in 2009 on the back of a coup, then skipped the following elections only to make a winning comeback in 2018.

As his opponents refused to campaign, he flew across the country by private plane, showcasing infrastructure built during his tenure.

Still, many seemed to have stayed away on Thursday.

Two hours before polls closed, at a polling station in an opposition stronghold in Antananarivo, an election official yawned. Another sat with his head resting on his hands.

Only 18 percent of those registered there had shown up. “It’s really not much,” said one official.

At another polling station in a poor district of the capital, officials told an AFP reporter during the afternoon that turnout was around 30 percent.

For many, politics takes a back seat to making ends meet.

“In the morning, I don’t eat — only a little at lunchtime and in the evening. Otherwise, I can’t get by, I don’t have enough,” Josiane Rasomalala, 41, told AFP.

“I’m voting because we need a better life.”

Madagascar has been in turmoil since media reports in June revealed Rajoelina had acquired French nationality in 2014.

Under local law, the president should have lost his Madagascan nationality, and with it, the ability to lead the country, his opponents said.

Rajoelina denied trying to conceal his naturalisation, saying he became French to allow his children to study abroad.

His critics were further enraged by another ruling allowing for a presidential ally to take over on an interim basis after Rajoelina resigned under the constitution to run for re-election.

They have also complained about electoral irregularities.

In Androy, southern Madagascar, “The polling stations are literally closed, there are no voters,” said Siteny Randrianasoloniaiko, one of two opposition candidates not taking part in the boycott.

Results should be announced on November 24.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP