“I am here to take you home. You are in a safe place” — Israeli soldiers are being carefully prepared to receive potentially deeply traumatised women and child hostages seized by Palestinian militants.

From a manual for trauma care to medical support, even the first words the soldiers escorting them home will say have been carefully scripted, with experts warning many could face a long road to recovery.

During a four-day truce agreed by Israel and Gaza’s Hamas rulers, 50 of the roughly 240 hostages held by the militants are set to be freed in exchange for 150 Palestinian prisoners.

The first of them are due to be handed over on Friday, after around seven weeks in captivity in a war-battered landscape.

At the request of the Israeli government, child abuse specialists from the Haruv Institute in Jerusalem prepared detailed guidelines on how to handle the minors once they are released.

“When the soldier meets the child,” reads the manual, seen by AFP, they should politely introduce themselves and offer soothing assurances such as “I am here to take care of you”.

Aside from immediate medical aid, they are encouraged to find out and carry with them a child’s favourite food items, be it pizza or chicken schnitzel.

If that is not known, the manual asks that they carry basic items such as bread, cheese and fruit.

With many of them having lost family members when Hamas launched the deadliest attack in Israel’s history on October 7, soldiers are instructed to sidestep questions from the children on the fate of relatives — even if they know the answers.

“Each question must be answered along the lines of ‘My job is to bring you to Israel, to a safe place, where people you know will be waiting for you and will answer all of your questions.'”

It recommends a “complete ban” on any media engagement with the children immediately after their release.

The manual drew from the experiences of victims in other hostage scenarios including victims of the Islamist group Boko Haram in Nigeria, said Ayelet Noam-Rosenthal, one of the authors.

“We need a common trauma-informed language for the children coming back,” Noam-Rosenthal told AFP.

“We need to do everything to do no harm,” she added, “to not cause additional trauma.”

Israeli experts warn there are several unknowns about the hostages to assess what kind of support will be needed.

“No one knows if kids and their parents will be released together or separately,” Moty Cristal, a retired Israeli military official with experience in hostage negotiations, said.

“We don’t know if women have faced sexual violence in captivity,” he told AFP.

“Given the barbaric nature of the attacks and captivity we can only prepare for worst case scenarios,” he added.

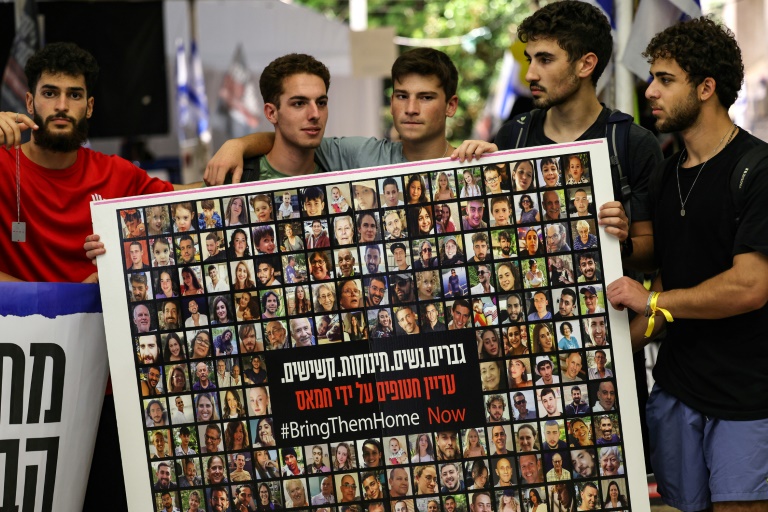

Relatives of the hostages have campaigned relentlessly in Israel and around the world for their release, holding public demonstrations, exhorting global officials to help and pursuing a vigorous media campaign.

AFP has confirmed the identities of 210 of the around 240 people abducted on October 7 during cross-border attacks by Hamas on military posts, communities and a desert music festival.

At least 35 of those taken hostage were children, with 18 of them aged 10 or under at the time of the Hamas attack.

“In some cases, children were taken moments after watching their parents being brutally murdered,” Zion Hagai, chairman of the Israel Medical Association, told the media.

“They are not only forced to live with this trauma but to experience it in a strange, dark and scary place.”

One of the youngest hostages is Kfir Bibas, a boy who was just nine months old when gunmen snatched him from Nir Oz kibbutz near the Gaza border, along with his four-year-old brother Ariel and his parents Yarden and Shiri.

Shiri appears in a video from the day of the attack seen by the family, cradling her children in her arms with gunmen all around her.

Some of the children have had birthdays in captivity.

At least 68 of those abducted were women, many of them aged over 80.

The Haruv Institute manual as well as health officials warn that professionals offering support are themselves vulnerable to trauma.

Ofrit Shapira-Berman, a psychoanalyst and professor at the Hebrew University, said she met a teenage boy at a counselling session for October 7 victims who heard his parents and two sisters screaming on the phone before they were murdered.

“I’m just sitting there and trying to grasp something out of my experience to help him,” she said in an online video, adding that the boy and other victims “will need our help for many, many years.”

“I do my best,” she said, “and then I go out and start weeping because it’s beyond imagination.”