The US Federal Reserve is almost certain to hold its key lending rate steady for a fourth consecutive meeting Wednesday, as inflation continues to inch closer towards its long-term target of two percent.

But analysts and traders will be looking beyond the headline figure — which is likely to remain unchanged — for any indication of how soon the US central bank could start cutting rates.

Following a post-pandemic surge in inflation, the Fed rapidly hiked interest rates in a bid to bring the price-increase measurement back down towards its goal of two percent — with surprising success.

In recent months, the Fed’s target inflation rate, which strips out volatile food and energy prices, recently fell below an annual 3.0 percent, while economic growth remained robust at 2.5 percent in 2023 and unemployment stayed close to historic lows.

“The data to date has been stunningly good,” KPMG chief economist Diane Swonk wrote in a blog post this week.

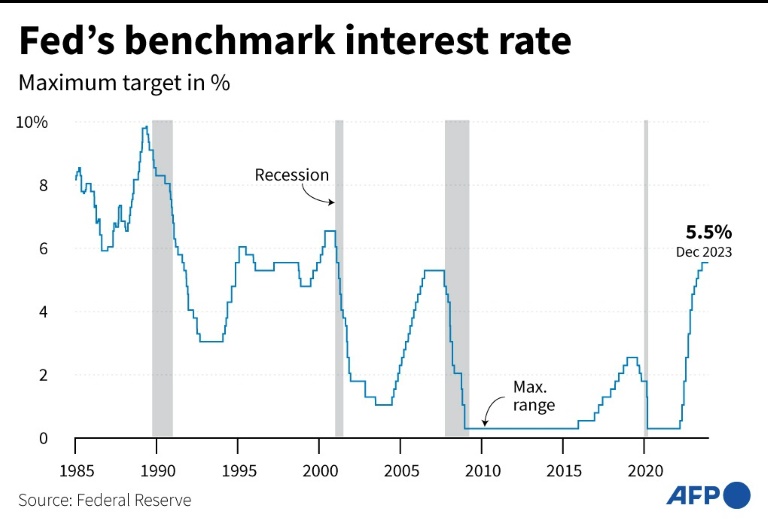

But despite the strong numbers, the Fed’s work remains unfinished. That is why policymakers on the rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) are widely expected to keep the central bank’s key lending rate unchanged Wednesday at a 23-year high of between 5.25 and 5.50 percentage points.

This week’s meeting should serve “to confirm that the FOMC has left behind its tightening bias and has more intensely begun the discussion around rate cuts,” Deutsche Bank economists wrote in a note to clients.

The hints could either come in the rate decision itself, or in Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference later in the day.

But Powell must also “be cautious to curb his enthusiasm at the press conference so that he does not inadvertently trigger a major financial market rally,” as happened after the last rate decision in December.

In its December meeting, the Fed raised its economic outlook for the year ahead, and signaled it expects as many as three quarter-percentage-point rate cuts in 2024, sparking a wave of optimism in financial markets that the central bank could cut rates as soon as March.

When the Fed lowers interest rates, US consumers usually get cheaper access to credit, meaning the cost of everything from car loans to mortgages becomes cheaper, while company valuations see a boost.

In response, a number of senior FOMC officials poured cold water on the enthusiasm.

“We are fully committed to restoring price stability and doing it of course as gently as we can, but we have a lot of work left to do,” San Francisco Fed Chair Mary Daly told Fox Business earlier this month.

And Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic told a conference that recent “unexpected progress” in the fight against inflation had led him to move up his forecast for the start of rate cuts from the fourth quarter of this year to the third.

“But the evidence would need to be convincing,” added Bostic who, like Daly, is also a voting member of the Fed’s rate-setting committee.

Heading into this meeting, traders and analysts were divided mainly between those who believe economic conditions are such that the first rate will come in March, and those who expect the Fed to tread more cautiously, and move in May instead.

“We retain our baseline expectation that the FOMC will initiate an every-other-meeting cutting cycle in March,” economists at Barclays wrote in a recent investor note, adding that their forecast was dependent on the Fed’s favored inflation measure continuing to come in weak.

Goldman Sachs Research also expects a March cut, “mainly because progress on inflation is already sufficient,” chief US economist David Mericle wrote in a recent note to clients.

Although futures traders initially leaned towards a March cut, they recently have dialed back their optimism, and now assign a less-than-50 percent chance that the Fed will move then, according to AFP analysis of CME Group data.

They are much more confident about the chances of a May cut, assigning a near-90 percent probability that the Fed will lower its key lending rate by at least 25 basis points on May 1.

“Our baseline remains no March FOMC cut absent weaker activity, but a cut at the 1 May FOMC meeting looks increasingly possible,” Standard Chartered head of North American Macro Strategy Steve Englander wrote in a note to clients.

AFP

AFP