What is an eclipse, how rare are they, and how can you best view this one? Chris Knight explains

Article content

In advance of the total eclipse of April 8, the National Post’s Chris Knight explains how this phenomenon works, where best to see it, and how to do so safely. Watch the video or read the transcript below.

On Monday April 8, North America will experience a total eclipse of the heart – no, wait, that’s just Bonnie Tyler. It’s a total eclipse of the sun.

Article content

This is a phenomenon in which the moon passes directly in front of the sun, blocking out its light and turning day, for a few minutes, into night. A solar eclipse shouldn’t be confused with a lunar eclipse, which is where the moon gets into the shadow of the Earth, making the moon look reddish or rusty brown. It’s cool, but you can usually see one or two a year from almost anywhere. Solar eclipses are much more rare and much more spectacular.

Advertisement 2

Article content

The reason for them is a cool cosmic coincidence. The moon is about 3,500 kilometres across and 384,400 kilometres from the Earth. The sun: 1.4 million kilometres across, and about 150 million kilometres away.

What this means is that the moon is 400 times smaller than the sun, but also 400 times closer. So, when they line up in the sky, not only does the moon perfectly cover the sun, it leaves just enough space at the edge to see the corona, the wispy edge of the sun’s outer atmosphere, normally invisible in the glare from the sun itself.

If the moon were any bigger (or closer), we’d lose the corona. Any smaller or farther away and it wouldn’t cover the whole sun. In fact, an annular eclipse is when the moon is too far out in its orbit to quite cover the sun, leaving a so-called ring of fire — it’s cool, but not as cool as a total eclipse, when you feel the temperature drop, birds will fall silent and people will find themselves shouting in awe.

On this scale, the moon would be about nine metres from the Earth, or about 30 feet. And the sun would be 3.8 kilometres away, and a little bigger than a hot-air balloon.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

Recommended from Editorial

Now, it’s true that almost all of North America will see a partial eclipse, where the moon covers a portion of the sun. But the sun is so bright that even covering up most of it does very little to its brightness. Think of a cloudy day – the sun is completely covered by clouds, but you wouldn’t think it was night.

Even Toronto or the northern part of Montreal, where you have 99 per cent coverage, you won’t get the whole show. The sun is about 400,000 times as bright as the moon, so if you cover up all but one per cent that’s as much light as 4,000 full moons. So it’ll get a little dim for a few minutes but it won’t get completely dark.

That all changes inside what’s called the path of totality. That’s where the moon completely covers the sun. This path is about 160 kilometres wide and it moves across the Earth at more than 2,000 kilometres an hour, meaning that from the ground you’ll have about three or four minutes of darkness.

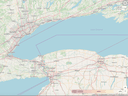

It will make landfall in Mexico, then travel northeast through Texas, Arkansas, Indiana, Ohio, then it crosses over Lake Erie and into Canada. There it covers St. Catharines, Niagara Falls and the area, just missing Toronto, passing over Lake Ontario and then roughly following the 401 from Port Hope all the way to the Quebec border, where it will cover the southern parts of Montreal. This will all be a little after 3 p.m. local time.

Advertisement 4

Article content

From there the shadow continues eastward over, Sherbrooke, Quebec, Fredericton and Miramichi, N.B., and Summerside, P.E.I.

St. John’s Newfoundland, will narrowly miss the show, but it will fall on a little rock called Eclipse Island near Burgeo, NL. It got its name from Captain James Cook, who was there during an eclipse on Aug. 5, 1766, and used the event to calculate his exact position on the Earth.

There are at least two solar eclipses every year, but because the path of totality is so narrow, they don’t come to the same place very often – about once every 375 years on average for a given spot. For instance, Toronto’s last total eclipse was Jan. 24, 1925, and its next will be Oct. 26, 2144. There’s one in 2099 that, like this one, just misses the city. And the next one anywhere in Canada isn’t even until 2044, over Western Alberta.

To view the eclipse, you’ll need one of two things. Eclipse glasses, made with special lenses that are darker than any sunglasses. They carry a certification, ISO 12312-2, and you need that because if you’re outside the path of totality, even looking at a sliver of the sun directly can damage your eyes.

Advertisement 5

Article content

If you don’t have glasses or time to get them, you can make a pinhole camera, which is just two sheet of paper or cardboard with a pinhole in one. Line them up so the sun shines through the hole onto the other sheet and you’ll get an image of the eclipse in progress.

Now, the great thing about totality is that, once the sun is completely covered by the moon, you can look at it with the naked eye, because there’s basically a giant rock blocking out all the harmful rays of the sun. The only caveat is that once totality ends in a few minutes, you’ve got to put your eclipse glasses back on or you’ll damage your eyes.

I’ve haven’t mentioned the biggest unknown for eclipses: Weather. If it’s a cloudy day, even in the path of totality, you’re gong to miss the show. Historically, April 8 in Southern Ontario has a 60% chance of being overcast. It gets a little worse the further east you go. So the best you can do is hope for clear skies.

Article content