There is no evidence that wars ever stopped during the Games, but the legend of an Olympic truce refuses to die

Article content

Mark Golden, a University of Winnipeg professor who died in 2020, was a leading Canadian historian of athletics in the classical world.

Before London hosted the 2012 Summer Olympics — its first since the postwar austerity games of 1948 — he published a paper, previously presented to fellow classicists at Ancient Olympia itself, titled “War And Peace In The Ancient And Modern Olympics.” It remains an eye-opener today, because it debunked but didn’t quite kill an Olympic legend that refuses to die.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

By sketching the history of the Olympics in times of war, he participated in the time-honoured tradition of discovering that the Olympic truce, like the continuity with classical antiquity embodied in the Games themselves, is a bit of a fuzzy myth. It is not really supported by any actual historical evidence, but it persists in the world’s shared sporting culture all the same. It is both real and imagined. But it is only real because it is imagined. Myths are like that.

“The past sleeps lightly at Olympia,” Golden wrote. His primary example was the notorious 1936 Berlin Games, and the documentary film released two years later by Leni Riefenstahl, the Nazi cinematic propagandist, with its famous image of a marble statue of a discus thrower coming to life, emphasizing the vital mythic continuity between the present and the classical past.

“In a misty landscape of ruined buildings, broken columns, and weeds run wild, a Greek temple stands amid the wreckage. Statues appear and then waken to life; a naked athlete throws a discus, another a javelin — this heads towards a bowl of fire. Another naked youth lights the Olympic torch and holds it high. It is carried from hand to hand in a relay and then reaches the stadium in Berlin,” Golden wrote.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“The message is unmistakable: there is a clear and close link between antiquity and the modern world, and especially between the ancient and modern Olympics. This connection has been forged by many besides the Nazis, before and since,” he wrote.

Golden’s point was wider than just this Fascist extreme. Every country considers itself an heir to the Olympian tradition, and this colours their view of war, of peace, and also of modern international competitive athleticism, famously described by George Orwell as “war minus the shooting.”

As the mythic past is set to reawaken this summer in France, Golden’s debunking is as poignant as ever. If there really was such a thing as an Olympic truce, shouldn’t we see some evidence of it? If we don’t, can we still call it a tradition?

The Austerity Games

Today there are wars in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, Myanmar, Niger, and many lesser military conflicts across the Americas, Africa and Eurasia. So the Paris 2024 Olympic Games will take place, as usual, against the backdrop of war. There will be calls for truce, and appeals to both modern and classical traditions, but the wars will go on, and so will the Games.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

For the modern Olympics, this familiar pattern has lasted through world wars, cold wars, holy wars, civil wars, illegal wars, and many other forms of warlike military conflict, such as in Ukraine today, which Russia euphemizes as a “special military operation.”

None stop because of the Olympics. If anything, wars cancel Olympics, not vice versa. The only three times they have ever been completely cancelled were during the First and Second World Wars. (Tokyo 2020 was delayed by the pandemic until 2021.)

But mostly, wars and Olympics don’t seem to affect each other all that much.

London was supposed to host them in 1944, but instead hosted in 1948, nicknamed the Austerity Games, from which Germany and Japan were excluded, and the Soviet Union declined to send a team, but did send observers.

West Germany was allowed in for Helsinki in 1952, as the Cold War Olympic era took off in the age of mass media. This marked the emergence of the Soviet Union as a sporting powerhouse, enabled by widespread disregard for amateur ideals in favour of industrialized athlete development and doping programs.

Advertisement 5

Article content

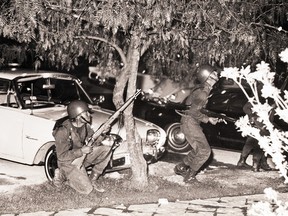

Mexico 1968 was particularly outrageous for a government’s use of military violence against its own people, with soldiers killing hundreds as they broke up a student protest a week or so before the Olympics. But they went ahead all the same.

Even in Munich in 1972, the catastrophic spectacle of terrorist murder before the world’s assembled media was not enough to cancel them.

It was an important political moment for West Germany during the Cold War, but is remembered primarily for the massacre of Israeli athletes by eight members of Black September, a Palestinian militant group. After killing two athletes in the Olympic Village and negotiating helicopter passage with nine others to an airport with a jet fuelled for Cairo, the hostage-takers returned fire on West German authorities, who botched a rescue operation, and the whole thing ended in a wild shootout in which hostages might even have been shot by police, a grenade blew up inside a helicopter, and all the hostages died.

There was diplomatic disagreement over the proper response for the Games, as the late George Jonas, the journalist and former National Post columnist, wrote in Vengeance, his book about the subsequent Israeli assassination campaign against the surviving terrorists, three of whom were arrested but released soon after in a hostage exchange.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Before the transfer to the airport, while the hostages were still in the Olympic Village and the first two had been murdered, West German Chancellor Willy Brandt “went on television to deplore the incident and to express his hope for a satisfactory resolution — and also to suggest that the Olympic Games should not be cancelled, which was what the Israeli government had requested to honour the memory of the two slain athletes. In Chancellor Brandt’s view, this would have amounted to a victory for the terrorists. It was certainly one way of looking at the matter — though to continue with the Olympiad, supposedly symbolizing brotherhood and peace, as if the murders were of no consequence could just as easily have been seen as a triumph for terror,” Jonas wrote.

After barely a day’s delay, the Games continued. Even the national flags did not stay down at half-staff for the duration, following protest by Arab states.

It remains an impossible dilemma. How can you play games in a time of war, death and destruction? On the other hand, how could you not, if you are to play them at all? Since the modern Olympics were reborn, there has never been a time when no countries were at war.

Advertisement 7

Article content

Talking about an Olympic truce as an ancient tradition has a noble pedigree among high-minded promoters of the Games, and among serious historians. “It has long been one of the central goals of the modern Olympic movement to work towards contact, understanding, and peace among nations,” Golden wrote.

The truce is not meant as some modern invention, but rather as a defining characteristic of the Olympic spirit. As evidence, the claim is often repeated that wars would stop during the ancient Olympic Games.

The founder of the modern Games, for example, French aristocrat Pierre de Coubertin, after many years as president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), spoke in 1929 of a “sacred truce” in which “all armed conflicts and all combat among Hellenes (Greeks) had to cease.” And it continues to the present day even in academic scholarship.

“Nevertheless, it is simply wrong,” Golden wrote. “There is no evidence that wars stopped for the Olympic festival, and no reliable classical source says that they did. In fact, since truces also accompanied the other three great pan-hellenic competitive festivals of the classical period — the Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean games — it is hard to see how the Greeks managed to be at war so consistently if the games had the effect (of requiring a truce).”

Advertisement 8

Article content

The Greek word that gets translated to “truce” in English is “ekecheiria,” literally “staying of hands” or “holding of hands,” and Golden writes that this ideal did give immunity from attack to the site of the Games itself, and to Elis, the city-state on the Peloponnese peninsula that hosted them at the nearby sanctuary to Zeus in Olympia. It also promised safe passage to people journeying there. If you want to crown a real champion, you have to let everyone compete, and they have to be able to get there. This was the Greek ideal. Offend it and you offend the gods.

Crimean Peninsula invaded days after Sochi 2014

But the supposed ancient Olympic truce no more stopped war between Greek cities Athens and Sparta in the late fifth century BCE than it stopped the war against the Persian invasion a few decades earlier. In both cases, the Olympic Games kept calm and carried on. If anything, the Games temporarily interfered with wars because the same young men were competing at both — but not because there was a goal of everyone laying down arms.

Despite all this, the modern myth of the Olympic truce runs deep in sporting culture. De Coubertin wrote in 1892, just before the modern Olympics began: “Let us export rowers, runners and fencers; there is the free trade of the future, and on the day when it is introduced within the walls of old Europe the cause of peace will have received a new and mighty stay.”

Advertisement 9

Article content

A hundred years later, after a century that contributed more than its fair share to the human history of warfare, the IOC explicitly took up the aim of the Olympic truce in 1992, and embedded it into the culture of global athletic competition.

United Nations motions to endorse the truce started shortly after, and today the UN describes the Olympic truce as “an expression of mankind’s desire to build a world based on the rules of fair competition, peace, humanity and reconciliation.”

The second fundamental principle of the Olympic Charter likewise states: “The goal of Olympism is to place sport at the service of the harmonious development of humankind, with a view to promoting a peaceful society concerned with the preservation of human dignity.”

Golden described a slight recent shift from the International Olympic Committee, which “has abandoned the claim that the ancient truce put a halt to war and expresses more modest ambitions — essentially, giving peace a chance — for the modern one too.”

So, if the modern Games are a revival, or even a continuation of this ancient tradition of peace, shouldn’t the Olympic truce have a strong grip on the behaviour of modern belligerents? It does not seem to.

Advertisement 10

Article content

If it is ever explicitly acknowledged at all by a country actually fighting a war, the supposed truce is usually either ignored or blatantly flouted, as, for example, when Russia invaded Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula four days after hosting the Winter Games at Sochi in 2014.

Sometimes, such as in the case of Russia launching all-out war on Ukraine mere hours after the torch went cold at the Beijing Games in 2022, it is devalued for purely strategic reasons, which is to say reluctance to anger the Chinese, rather than offend the Olympic spirit, let along the Olympian gods.

In that case, there was a United Nations call for a global truce, but Canada had not signed it. Instead, and against the wishes of Canadian Olympic officials, Canada joined a wider American-led diplomatic boycott of the Beijing 2022 Games in protest at China’s mistreatment of the Uyghur Muslim minority in Xinjiang province through mass detention, forced sterilization, religious suppression and other practices, which Canada regards as genocide.

It wouldn’t have mattered if Canada had signed the UN global truce document, however. War continues through the Olympics because no country is ever truly bound by an imaginary truce.

Advertisement 11

Article content

In a way, this might seem fitting for the modern Olympics, a Hollywood pastiche of lavishly reimagined classical history. But remakes are never originals, and today’s athletes don’t compete naked. The central and most iconic trappings of the modern Olympics are thoroughly modern.

The Olympic podium, for example, was popularized at the Los Angeles Games in 1932, allowing the glory to be shared in a tiered system, quite unlike the original. The Greeks had no prizes for second place, let alone third. You either got the olive branch crown or you lost. Smoky, the terrier, was also the first Olympic mascot that year.

Curiously, the motto, “citius, altius, fortius,” meaning “faster, higher, stronger,” wound up in Latin, not Greek. Like the rings, this motto was invented under the guidance of de Coubertin, an idealist who drew inspiration from the Victorian culture of self-improvement. His enthusiastic interest in education reform and his affection for the robust physical education program at the Rugby School in England meant there is almost as much Victorian England in the modern Games as there is Ancient Greece.

Advertisement 12

Article content

For example, the famous “Corinthian spirit” that the modern Games are said to embody, of amateurs pursuing athleticism for its own sake and for the glory of fair competition, no matter who wins, is similarly modern.

Despite how it sounds, the name does not come from classical antiquity, and has nothing to do with the ancient Greek city Corinth or the ornate style of marble column, but rather from the former Corinthian Football Club in London, which had a famous reputation for amateur fair play and good sporting spirit, quite unlike the ancient Greek competitive spirit of winner take all.

The marathon really does draw on ancient Greek military history, inspired by soldier Pheidippides’s legendary fatal but successful run from Marathon to alert Athens of the Greek military victory and a looming Persian naval attack. But it was not run at the ancient Olympic Games. In fact, the modern official distance of 26.219 miles was set at the 1908 London Olympics, symbolically representing the approximate distance from Marathon to Athens, but more specifically marking the distance from the starting line at Windsor Castle to the stadium at White City, with a final lap toward a finish line in front of the royal box.

Advertisement 13

Article content

So, sometimes the past and the present get mixed up and confused. That is more or less what happened with the truce.

It’s not the only way to promote peace at the Olympics. There are other options. Boycotts became the primary tool of Olympic diplomatic peacemaking efforts in the 1980s, as the Cold War roared along, the fall of communism not yet inevitable or even obviously possible. First came the American-led boycott of the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow, in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, supported by nearly 70 countries, including Canada. Then, in 1984, came the retaliatory Soviet boycott of the Los Angeles Games, supported by a smaller group of countries.

Olympic boycotts

North Korea boycotted Seoul in 1988, supported by Cuba, the last major boycott until the diplomatic one against Beijing in 2022.

Today, though, the idea of an Olympic boycott seems quaint and outdated. If North Korea, of all countries, can get over itself and send a delegation to march with South Korean athletes, even to the 2018 Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea, then surely boycotts have proven their futility.

Advertisement 14

Article content

The Olympic truce is a more durable concept.

For something that is supposedly as old as Western civilization, however, the actual explicit declaration of a truce comes quite late in the history of the modern Olympics.

It was introduced by the IOC in 1992, along with an effort to let athletes from the former Yugoslavia compete under the Olympic flag at Barcelona. Two years later, the United Nations had endorsed it, and Juan Antonio Samaranch, the IOC president, issued a powerful plea at Lillehammer, Norway, for a ceasefire in Bosnia.

“Please stop the fighting. Please stop the killing. Please drop your guns,” he said.

Sarajevo, which had hosted the Winter Games a decade previously, was under siege. Genocide would come to Srebrenica the following year, in the massacre by Serb forces of more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys. But there was some positive peacemaking effect, even beyond the symbolic declaration and the drafting of the United Nations resolution, which is endorsed over and over again for each new Games. A brief ceasefire is credited for allowing 10,000 Bosnian children to be vaccinated.

Advertisement 15

Article content

The late Gerald Owen, an editor and writer for the Globe and Mail, and previously for the National Post, wrote this in 2004 before the Athens Games: “It’s easy to pooh-pooh the peace-making quality of the Olympics, but the ancient games did more than anything else to create a self-conscious community of hundreds of independent Greek city-states. Though the Olympics certainly did not make the Greeks into pacifists, the Olympic truce during the games was sacred, setting real limits to chronic warfare. Breaches of the truce were a serious offence against the gods. Unlike the ancients, we moderns have aspirations to perpetual peace, but our world wars did not pause for the Olympics; 1916, 1940 and 1944 had no Games. Zeus, Apollo and their colleagues had a better peace-making record. The ancients feared and revered their gods (though they also made fun of them) more than we respect our own idealism.”

In his paper, Golden is more skeptical about this “self-conscious community,” and thinks even this might be a Roman invention, promoting their own ideal of a unified empire of diverse peoples, as against the warlike Greek reality.

Advertisement 16

Article content

“The term panhellenes (literally “all Greek,” meaning all the Greek city-states seen together as a whole) is rare in Greek before the Roman period. It may in fact reflect a Roman effort to create a history of Greece in a convenient image — just as our own usage betrays a desire to idealize a Greek world we often view as the foundation of our own,” Golden wrote.

It’s worth remembering, as the world slouches toward Paris, with guns still firing and countries fighting around the world, that Greeks just didn’t get along with each other as much as we like to think, even during their Olympics.

The whole world is like that today, the same as it ever was.

Recommended from Editorial

Article content