As housing stock dwindles across the country, researchers are worried about a concentration of homeownership among those looking to build wealth by buying more houses

Article content

By 2021, Ryan Fehr had grown tired of renting.

Article content

Fehr, 40 and a single dad, had just broken up with his girlfriend. He found there was no limit on how much landlords could raise the rent in Calgary, and he yearned to put down some roots in a house, especially for his then-two-year-old son, whom he had with his previous partner. It was also the middle of a pandemic. House prices were falling. Fehr felt he had a shot at earning his place in the vaunted club of homeownership.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Fehr is a foreman at a mechanical company that offers retrofit services, including plumbing and gas, earning an income of just under $100,000 a year. As the closure of daycares during the pandemic made it more difficult to care for his child, consequently threatening his employment, he slowly warmed to the idea of living with his parents who could help with child care while he saved enough money to buy a home.

Although Fehr considered himself fortunate to have the option of living in a house owned by his parents, the idea continued to gnaw at him. He felt embarrassed. But his situation would be temporary, he thought, allowing him to have his own place. In 2021, Fehr moved into his childhood room while his son occupied his brother’s. Then, almost a year later, the hunt began.

Fehr scoured several apps, scrolling through listings every day. He went on a few viewings. There was one house in Tuscany, with an offering price of around $380,000. But a day later, his broker told him the house was sold for $50,000 above its asking price. As days ticked by, prices began rising. Fehr looked as far as Cremona — only to be disappointed by the price and state of the property. Then there was the issue of commuting.

Advertisement 3

Article content

“Being a single dad, getting up every day and driving him an hour to child care out there wasn’t feasible,” Fehr said.

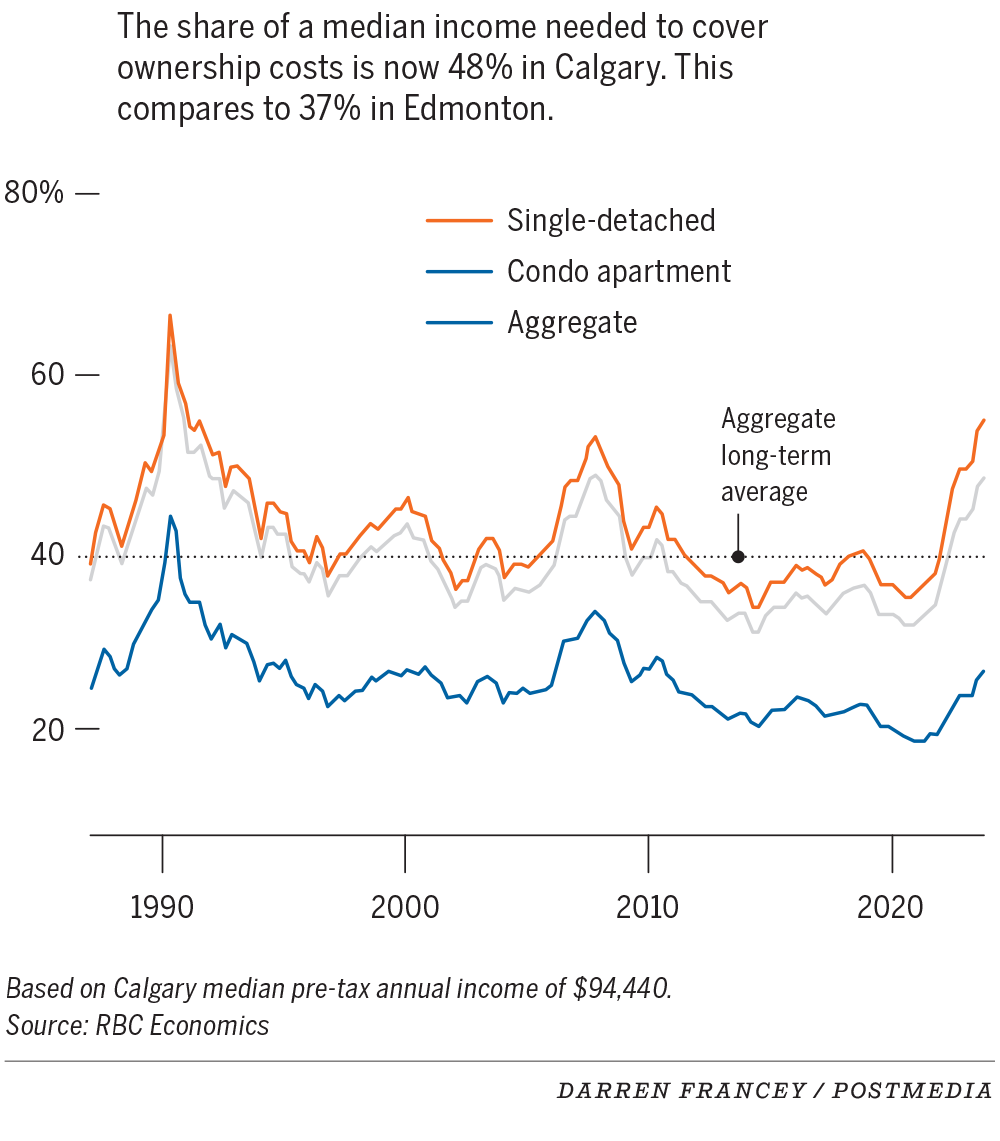

Property values started ballooning, in some cases exceeding $500,000. “When you’re a single guy trying to work, it’s not feasible, man, you’ll just be house-poor.” Fehr stopped scanning the apps, knowing he’d have to shell out nearly half or more of his income to afford an average house in Calgary. “I’m not out buying extravagant things and being crazy with my money. I have a good job. I have a career.”

What seemed like a temporary stay at his parents’ home would turn out to be much longer. Two years after his search began, he has given up the goal of homeownership. “We’ve been kind of renovating the basement, just so I can make it like an in-law suite,” he said. “I can live in the basement, and when (my parents) get old, they can live in the basement, and I’ll take the house.”

Stories like Fehr’s are becoming increasingly common in Alberta as house prices explode.

‘It just suddenly became like a Tesla stock’

An Ipsos poll in 2022 found that 63 per cent of Canadians who don’t own property have given up on home ownership. While the dream of owning a house was fading across Canada, Alberta, due to its unique boom and bust economy, long stood as an outlier with prices within reach of many residents. But as the price of oil surged, the province was flooded with people from across the country and around the globe who also wanted to escape the skyrocketing living costs in their cities.

Article content

Advertisement 4

Article content

For instance, property prices in February spiked by 23 per cent in a year. The price of a single detached home in Calgary has more than tripled since 2000, while a townhouse has nearly quintupled in the same period, according to the Calgary Real Estate Board (CREA). More than half of Albertans in the same Ipsos poll said they have stopped trying to buy a home.

Conversations about the causes of soaring housing costs usually revolve around a widening gap between demand and supply. Some reasons for the unbalance include lengthier permitting processes, long construction periods and higher costs for labour and building materials due to higher inflation.

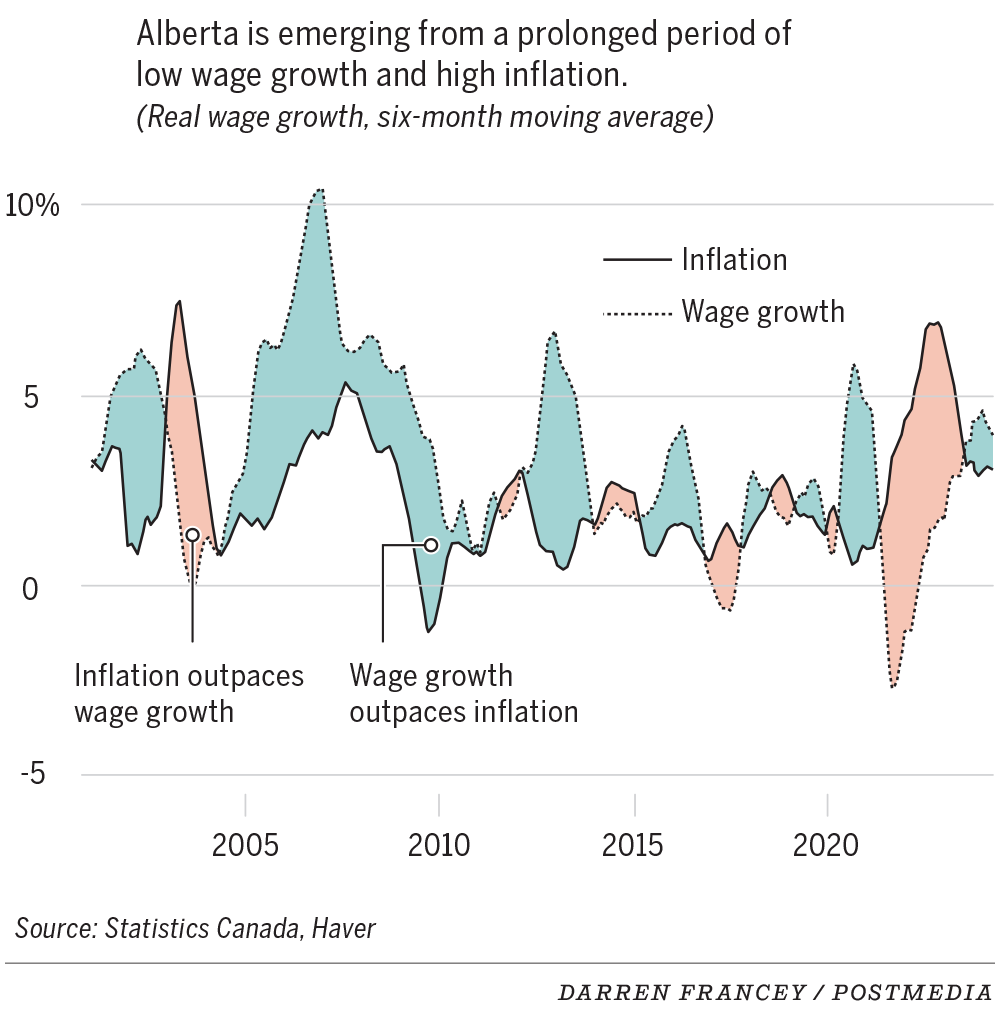

As wage growth lags severely behind price increases, many prospective buyers, like Fehr, are hoping for a drop in property values to realize their dream. But mention falling property prices to many homeowners and watch them grow anxious. It is why promising to lower house prices is billed by many as “political suicide”: any well-meaning effort to make homes more affordable conflicts with the interests of homeowners.

Advertisement 5

Article content

The transformation of homeownership and what it means through several economic and public policies, experts say, has fuelled a crisis that has put housing out of reach for many Albertans.

“For a long time, the idea of owning a home was seen as a means for housing stability and security of tenure,” said Andy Yan, director of the City Program at Simon Fraser University.

“Then it just suddenly became like a Tesla stock.”

Researchers say the shift arrived in the late 1980s.

But first, let’s rewind to the 1960s.

Homeownership as a financial safety net

Calgary was swelling. In four years, it gobbled up several communities, including Midnapore, Forest Lawn, Montgomery and Bowness. More than 450 oil companies set up their bases in the city. The population grew by 22 per cent to 320,000 from 1960 to 1965. Also growing was government spending on housing.

Social housing in Canada, largely funded by the federal government, grew tenfold in the mid-1960s, setting the stage for three decades of active public policies in the area. The government was building between 20,000 and 30,000 units of social housing across the country every year.

Advertisement 6

Article content

As researcher Greg Suttor writes in his book, Still Renovating, the climate of opinion was that governments could largely “solve” poverty and that welfare subsidies, which reached their zenith in the 1960s, shouldn’t just be for the elderly or ill but should offer security to the broad middle and lower-middle class.

The 70s saw a rise in community housing, such as co-ops, where people of different income levels lived as neighbours, allowing operators to offset the costs of subsidized units. Most of Alberta’s current stock of affordable housing units was built during those two decades.

Then Canadians were hit by skyrocketing inflation and double-digit interest rates on mortgages.

In an attempt to tamp down inflation and reduce federal deficits, which at one point reached eight per cent of the country’s GDP, Brian Mulroney’s government in the 1980s made several budget cuts, including slashing funding for affordable housing, child care and rental programs. As welfare subsidies were in free fall, the government introduced various incentives to buy homes while slackening rules to qualify for mortgages.

Advertisement 7

Article content

This period marked a turning point in the country’s dominant political ideology.

Its new philosophy was that instead of relying on government welfare, one must consider their home, savings and investments as a financial safety net; proponents argue such an ideology promotes an entrepreneurial spirit.

On the contrary, Yan said the accumulation of assets among the public was a state-sponsored initiative.

“We think, ‘Oh, this is all independent of public support and public money,’ when the fact of the matter is that it is completely due to it — just the accounting and streams shifted,” he said.

Recommended from Editorial

-

Squeezed: Navigating Calgary’s high cost of living

-

Feeling the sting of Calgary’s cost of living? Tell us how you’re managing

-

‘Food insecurity is at a crisis point’: Advocate argues policy changes are needed

-

‘You just can’t afford to be a single parent anymore’: Working mom struggles to afford necessities

-

Calgary used to be regarded as affordable. Now, that advantage is slipping away

Promoting an entrepreneurial spirit in the ’80s

Various policies that came along since the 1980s, such as reducing the minimum down payment to qualify for a mortgage, allowing withdrawals from tax-sheltered investments such as RRSPs for first home purchases, and offering tax exemptions for investors buying second properties to rent out, made homeownership attractive.

Advertisement 8

Article content

The government also introduced financial products offered by banks that pooled a bundle of property loans and sold them to investors.

These products, called mortgage-back securities, allowed investors to profit from the interest households paid on their mortgages. If homeowners were to default on their payments, investors would continue to receive their returns from the Canada Housing and Mortgage Corporation — a Canadian Crown corporation created in 1946 that administers several housing programs — which insured the mortgage.

“The spending that would have been done on non-market housing shifted towards a subsidy for homeownership,” Yan said. “It was subsidies in terms of mortgage insurance and assurances to the bank that people were able to pay their money back for these mortgages.”

Such products allowed banks to sell their risk to other investors and replenish their cash reserves, freeing up their capacity to lend to more households.

Efforts to increase homeownership became more aggressive in the 2000s.

The government bought groups of such housing loans — which had been packaged into financial products for investors — and offered them back to the public as guaranteed bonds, encouraging more people to invest in the real estate sector.

Advertisement 9

Article content

A few years later, the government stretched amortization periods up to 40 years. Mortgage insurance fees were slashed, and CMHC was allowed to insure interest-only, no-downpayment mortgages, incentivizing banks to lend money to a greater number of people. As a result, even people with insecure jobs had access to mortgages, albeit at the cost of very high levels of debt.

Albertans bought into the lure of homeownership. The ratio of homeowners to renters in the province grew from 62 per cent in 1986 to 73.5 per cent in 2006.

House prices rose as demand climbed.

“Those who could become homeowners, did, but then those who couldn’t, because of X-number of circumstances, were now locked out with none of the benefits,” Yan said.

Then the 2008 global financial crisis marked a reversal of such incentives. Mortgage requirements were tightened, and longer amortizations were scrapped, making it harder for people with lower incomes to qualify for housing loans.

More opportunity for investors, existing homeowners

A fall in demand among lower-income earners failed to bring prices down. The reasons include a lower housing supply amid rising population — thanks to high levels of immigration — and a growing appetite among real estate investors.

Advertisement 10

Article content

Following the crisis, to spur the economy, the federal bank kept its overnight rate at one per cent, prompting commercial banks to lower rates for a five-year mortgage to an average of 5.5 per cent. Low interest rates and tougher qualification criteria made it easier for those in relatively stable financial conditions — mainly investors and previous homeowners who could leverage their capital — to buy more homes while making it harder for people with low incomes to enter the housing market.

Information about the share of those owning more than one property in Alberta is not readily available to the public. However, the number of first-time home buyers has been falling across the country.

The share of mortgages purchased by the cohort fell by six percentage points in the third quarter of 2023 to 44.5 per cent from 50 per cent in 2014, according to the Bank of Canada. Meanwhile, the slice of housing loans bought by investors grew to 25 per cent. Repeat buyers now comprise nearly a third of the purchases.

Also — for the first time in four decades — the ratio of homeowners to renters in Alberta fell by 2.7 percentage points in 2021 to 70.9 per cent from 2011. There are other reasons for the drop, including the 2014 oil crash, which sparked an exodus of people from the province, pinching demand and pushing house prices relatively low.

Advertisement 11

Article content

But as oil prices have climbed, newcomers have flocked to the province. What’s different this time is that many of them are moving not just for economic opportunities but because living in other major cities has become unaffordable.

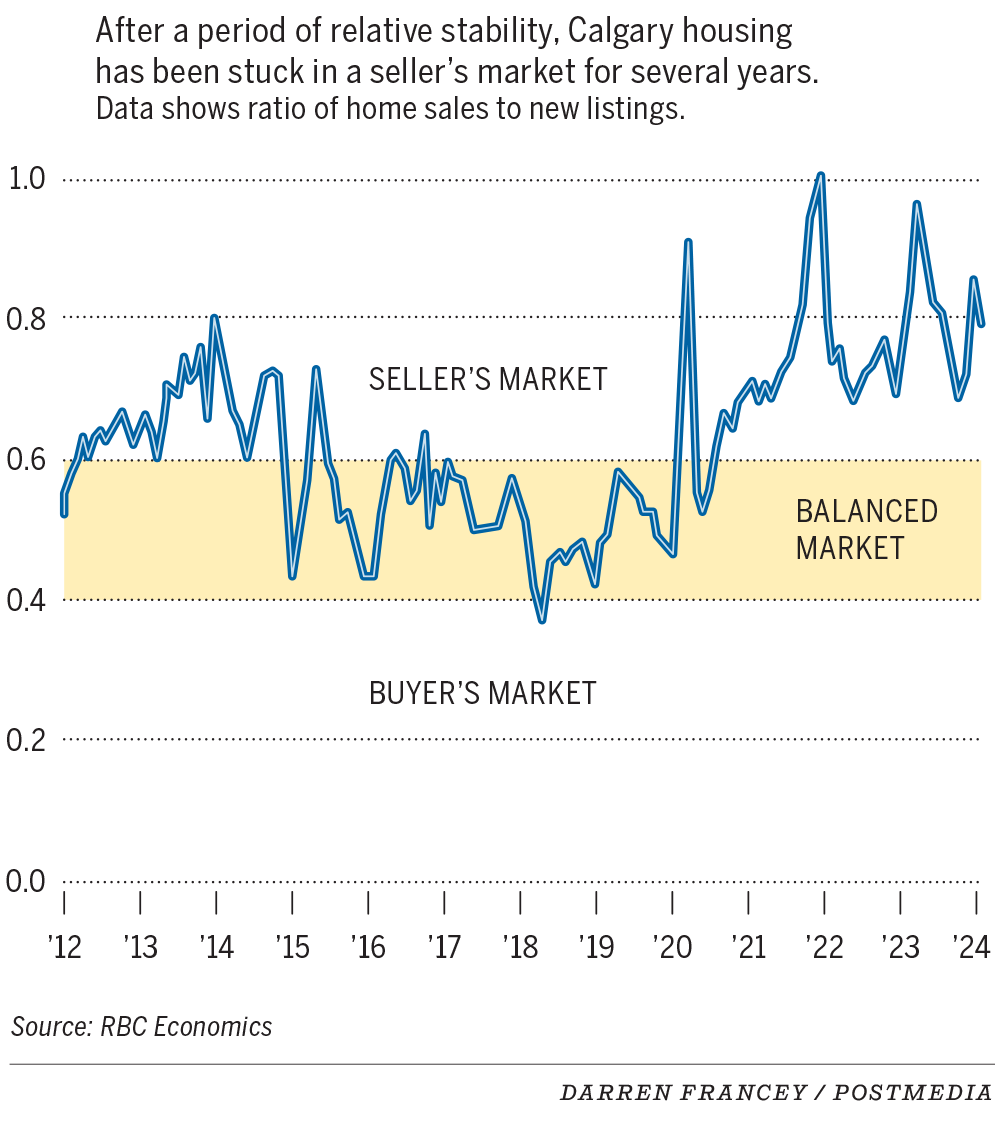

A jump in demand for housing in Calgary has spelled opportunity for existing homeowners and investors across the country.

“We have noticed that purchasers headquartered in Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, etc., who don’t have any real estate holdings in Calgary are taking a keen interest in entering our market and we’re getting calls from these types of groups every week,” said Mason Thompson, an analyst with Avison Young.

Many of these investors are also providers of rental services. However, that doesn’t necessarily translate into more affordability for the public.

Tenants across Canada end up paying about 170 per cent more in rent than the average rate for new purpose-built rentals, according to research by Steve Pomeroy, adjunct professor and senior research fellow for the Centre for Urban Research and Education at Carleton University.

Advertisement 12

Article content

‘It’s a challenge between have-nots and the have-mores’

Meanwhile, more competition has strained the budgets of people looking to buy houses for a place to live.

Jamil Thobani, a realtor in Calgary, said almost all properties he has sold were bought above their listing price, and nearly half of his clients are from outside the province.

“I’m telling you, there is a sense of frustration,” Thobani said. “It’s like, ‘Ah, we lost that one or we lost another one, we’re not going to find another place. Okay, my lease is coming up. I need to get out of this.’ Then they will maximize whatever they can and outbid the next person.”

As housing stock dwindles across the country, researchers, including Yan, are worried about a concentration of homeownership among those looking to build wealth by buying more houses.

“Right now, it’s a challenge between have-nots and the have-mores,” said Yan.

This is why relying merely on increasing the supply of homes is misguided, said Policy Alternatives economist Ricardo Tranjan. He said the solution also involves providing more affordable and accessible housing to people who need it the most.

Advertisement 13

Article content

In 2017, the federal government’s role in making housing more affordable saw a revival of sorts in the form of the National Housing Strategy. The government promised to spend $40 billion over the next decade through several programs aimed at increasing the supply of market, community and affordable housing. A part of the funding was also used for incentives to increase homeownership across the country. Seven years later, in April, the federal government launched another strategy — Canada’s Housing Plan — which envisions 100,000 new affordable housing units and repairing 300,000 existing units.

Other federal efforts include increasing mortgage amortization limits to 30 years, funding programs for the construction of rental apartments and non-profits to buy such units, tax incentives for builders, and eyeing under-used federal land to build new homes. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called it the “most comprehensive and ambitious housing plan ever seen in Canada.”

Although a step in the right direction, Tranjan said the initiatives do not alter the structure of the housing market.

Advertisement 14

Article content

“There is nothing we’re doing at the federal, provincial or municipal levels that will move us away from an asset-based economy,” Tranjan said. “(Most of what) we’re doing is increasing supply, but how much of this supply will be at a reasonable price and be purchased by someone who is not a homeowner looking for an investment property?”

As housing becomes more inaccessible for a larger number of people, Fehr wonders where he’d be if his parents didn’t own a house.

“If I didn’t have my folks, I’d be screwed,” he said.

Parental wealth does play an important role in the household wealth of adult children, now finds a report by Statistics Canada.

The study, which does not consider adults whose parents don’t own a house, divides parental housing wealth into three terciles or groups: lowest, median and highest.

Say you’re a Calgarian born in the 1990s and are earning between $60,000 and $120,000 a year, but the housing wealth of your parents fell in the lowest tercile — the study finds the value of your house on average will be $48,000 less than someone earning the same income but whose parental wealth is in the highest tercile.

Advertisement 15

Article content

The difference in Toronto is $117,000.

“This result reinforces the findings … that parents’ housing wealth may play a larger role in high-priced markets than in other parts of the country,” the report stated.

“In less expensive areas, where parents’ financial support may be less important for the purchase of a house, such as in rural areas and smaller urban areas, the differences in children’s property values associated with parental housing wealth are smaller.”

It means that, as home prices rise, the gap in wealth between adults with richer parents and those with poorer parents will also widen.

“I don’t think my dad would ever be qualified for the house we’re in now if we had a similar situation back then,” Fehr said.

“I’m grateful I’m here, but it’s depressing being a 40-year-old stuck at home.”

We know the rising costs of groceries, mortgages, rents and power are important issues for so many Calgarians trying to provide for their families. In our special series Squeezed: Navigating Calgary’s high cost of living, we take a deep look into the affordability crisis in Calgary. We’ve crunched numbers, combed through reports and talked to experts to find out how inflation is impacting our city, and what is being done to bring prices back to earth. But, most importantly, we spoke to real families who shared their stories and struggles with us. We hope you will join the conversation as these stories roll out.

Advertisement 16

Article content

This week: Priced Out: The Rising Cost of Housing

Still to come:

- June 3 to 4: The Cost of Doing Business

Our series so far:

Article content