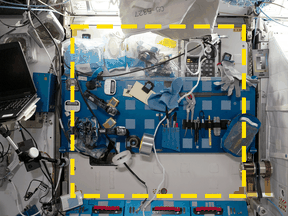

The ‘dig’ aboard the International Space Station involved photographing metre-square sections of the ISS to study its ‘material culture’

Article content

In what has been deemed a scientific first, a team led by Dr. Justin Walsh of Chapman University in California and Dr. Alice Gorman of Flinders University in Australia — and aided by some helpful astronauts — has carried out an archeology dig of sorts on the International Space Station, 400 kms above the Earth.

The study involved a space-age version of an age-old archeology technique, the “shovel test pit,” which helps scientists understand the overall characteristics of a dig site quickly through sampling. In the traditional version, a site is mapped with a grid of one-metre squares, some of which are selected for initial excavation to understand the makeup of the entire site.

Advertisement 2

Article content

In the space station version, scientists marked out a half-dozen metre-square sections of walls in various areas of the space station. They then commissioned astronauts on board to take daily pictures of the areas over a 60-day period in early 2022, first at the same time of day for 30 days, then at a random time of day for the second half of the experiment. These images were then studied, with scientists noting what objects appeared in each image, and how they were used.

The results provided some surprises. The team’s research found that one area studied, which was designed for equipment maintenance, was actually used not for repairing equipment but for storing it. Meanwhile, another area with an undesignated use was clearly being employed for personal hygiene activities, perhaps because it was near the station’s exercise equipment and one of the latrines.

Recommended from Editorial

Just like on-Earth archeology, there was missing data that required inferences to be made. For instance, the scientists asked NASA for access to the ISS Crew Planner, a computer system that shows each astronaut’s tasks in five-minute increments. When that was refused, they turned to the ISS Daily Summary Reports, published by NASA on its website.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

Though less precise than the crew planner, “they also more clearly represent the result of simply observing and interpreting the material culture record,” the team wrote in their paper, “Archaeology in space: The Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment (SQuARE) on the International Space Station. Report 1: Squares 03 and 05,” which was posted to the research web site Plos One.

It may seem odd to refer to “culture” when referring to a space station, but the ISS represents humanity’s first long-term off-world home — “a microsociety in a miniworld,” as a 1972 paper by the National Academy of Sciences Space Science Board referred to the then-future concept. Continuously inhabited for more than 23 years, the ISS has had a combined population of 270 people from 23 countries over that time.

“While it is possible to interview crew members about their experiences,” the team wrote, “the value of an approach focused on material culture is that it allows identification of longer-term patterns of behaviors and associations that interlocutors are unable or even unwilling to articulate.”

Advertisement 4

Article content

The archeologists noted that “square 03,” intended for equipment maintenance, “has instead become the equivalent of a pegboard mounted on a wall in a home garage or shed, convenient for storage for all kinds of items — not necessarily items being used there — because it has an enormous number of attachment points.”

They added: “Designers of future workstations in space should consider that they might need to optimize for functions other than work, because most of the time, there might not be any work happening there. They could optimize for quick storage, considering whether to impose a system of organization, or allow users to organize as they want.

Similarly “square 05,” seemingly just one side of a passageway for people going to use the lifting machine or the latrine, to look out of the cupola, or get something out of deep storage, had evolved into a storage place for toiletries, resealable bags and a computer that never (or almost never) gets used.

“It was associated with computing and hygiene simply by virtue of its location,” the team wrote, “rather than due to any particular facilities it possessed. It has no affordances for storage. There are no cabinets or drawers, as would be appropriate for organizing and holding crew personal items. A crew member decided that this was an appropriate place to leave their toiletry kit for almost two months. Whether this choice was appreciated or resented by fellow crew members cannot be discerned based on our evidence, but it seems to have been tolerated, given its long duration.”

Advertisement 5

Article content

They added: “A question raised by our observations is: how might a function be more clearly defined by designers for this area, perhaps by providing lockers for individual crew members to store their toiletries and towels? This would have a benefit not only for reducing clutter, but also for reducing exposure of toiletry kits and the items stored in them to flying sweat from the exercise equipment or other waste particles from the latrine.”

Clearly, there is much work still to do in the realm of space archeology. One can imagine future archaeologists combing through the Apollo landing sites on the moon, or examining the skeletal remains of long-dead Mars rovers.

For now, the team writes: “Our work fulfills the promise of the archaeological approach to understanding life in a space station by revealing new, previously unrecognized phenomena relating to life and work on the ISS. There is now systematically recorded archaeological data for a space habitat.”

Article content